Essential Teachings

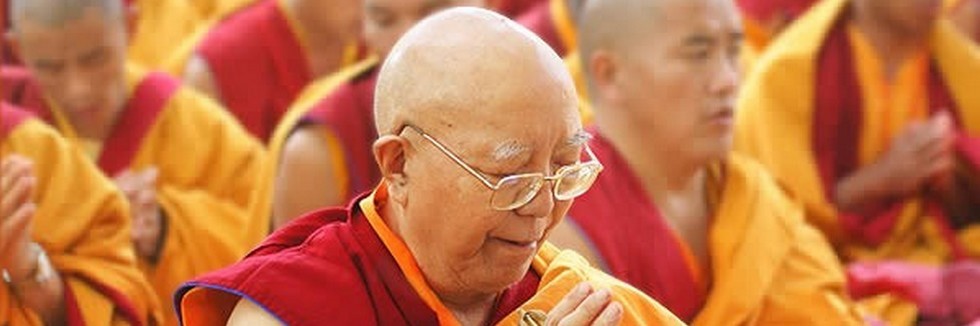

His Eminence the Third Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche,

Karma Lodrö Chökyi Senge

During these lectures I wish to discuss the view, meditation, and action in the Buddhist tradition in general. The teachings are very vast and profound. In order to be able to integrate them correctly in one's life, one must proceed by learning the view, by meditating the instructions, and by acting in accordance with the view. All three aspects need to be present.

First Talk

There are 84,000 general teachings of the Buddha. They all deal with instructions on becoming free from the three initial mind poisons, which are ignorance, attachment, and aversion. There is what is known as the Three Baskets of teachings that show how to become free of these poisons. These Three Baskets are presented in the three vehicles. They are: discipline, meditation, and wisdom. They are practiced so that disciples develop the three wisdoms won from hearing, contemplating, and meditating and engender the correct view, meditation, and action. The three vehicles are explained in the Three Baskets of teachings and are summarized as the two truths: the relative and the absolute truth. The relative truth concerns the general way the world appears to an apprehending mind. The ultimate truth concerns seeing the true nature of appearances and isn't a negation of the way things are perceived and apprehended. Specifically, Mahayana practice is carried out so that one sees that there is no contradiction between the relative and ultimate truths, i.e., there is no difference between the methods of practice and superior knowledge of the view. The Buddhist view is free of the false notions that are extreme views, which are believing that things exist forever or of their own accord and believing that things do not exist at all. This does not imply that another belief system is set up in Buddhism, rather it means becoming free of extreme views and seeing things as they really are. Freedom from nihilism doesn't mean one believes in eternal existents and freedom from eternalism doesn't mean one believes that nothing exists. The Buddhist view is being free of contradictions that false assumptions entail.

We understand the ultimate truth as a description of the true nature of all things, which lack eternal existence and are therefore not everlasting. Lacking eternal existence doesn't mean appearances and experiences don't exist. Things appear clearly and they function. The true view means seeing the display of the relative and ultimate truths, seeing that things appear clearly because they lack inherent existence. The ultimate nature of appearances and experiences does not obstruct things from appearing when causes and conditions come together.

Many of you have probably received these teachings and have heard them many times, but some of you may be hearing them for the first time, so I thought it might be helpful to introduce you to the two truths. I see the big fan you gave me as big and so do you. There is a truth to this, which is relative. We agree that it is a big fan. Tibetans call a fan lung-yab, lung meaning 'air' and yab meaning 'to swing.' When one investigates the fan and sees what it consists of, one will never be able to prove that the fan exists as swinging air. Lung-yab is merely a connotation that describes how this object functions. Nothing to a fan can be said to truly be lung-yab, which is the ultimate truth that there is no truly existing swinging air but only a coming together of many things to describe this object conventionally. The fan lacks true existence and does not uphold the term used to describe it. The ultimate truth does not deny the existence of the fan which serves the purpose of fanning the air so that it is cooler here. Both the relative and ultimate truths co-exist. This is valid for any other appearance, too. It is also true for the mind.

This brief explanation is meant to help you understand the Buddhist view, which is freedom from assumptions about eternalism and nihilism. In some sense, we shouldn't even speak about the Buddhist view, but we do because that is what Buddhists talk about. The view isn't Buddhist and isn't somebody's view - it is simply the way things are. Some people believe in eternalism and others believe in nihilism and the Buddhist view is beyond such wrong views. The idea of freedom beyond the wrong views should not become a belief one simply accepts, rather it should be understood correctly. I am not speaking about something you must believe without investigating for yourself. One should know and find the correct view for oneself. Then one is in an easier position to engage in the practice and to live one's life in accordance with the view, i.e., to practice the methods together with superior knowledge of the two truths as to how things appear and how they are. The view that is free of the extremes needs to pervade one's practice of the ground, path, and fruition of the Buddhadharma, the reason why a correct understanding is very important. It is of utmost importance to understand that the two truths are not contradictory but are indivisible, otherwise one can become confused when starting to study the Sutras and commentaries. Having the correct view makes it easier and less confusing to practice the path. There is a saying in Buddhism that someone who has not heard and understood the teachings but tries to practice is like a person trying to climb a cliff without hands and someone who has understood the view but doesn't practice is like a person who returns from an island filled with jewels empty-handed.

Questions & Answers

Question: "Your Eminence. From the point of view of relative truth, when one is hot, one swings the fan and cools off. From the point of view of ultimate truth, when one is hot, one swings the fan and cools off. So a lazy man may ask, why bother looking for ultimate truth? What's the difference?"

Rinpoche: Probably there is a little confusion as to what I was talking about, using the lung-yab as an example. As far as the nature of the fan is concerned, yes, relatively there is clinging to the idea that it is a fan that swings and brings refreshing air. But when you examine it carefully, there is no such thing as a unique entity that is a fan. And if you understand and realize the ultimate truth, there is no such thing as heat that you can identify as an independent existent. That is the ultimate nature of heat; it lacks true existence. Having realized this, there is no need for a lung-yab, an 'air swinger.'

Same student: "Your Eminence. I would like to pursue this question further. It seemed to me that the thrust of it was, how does the perception of ultimate truth alter one's experience? Does it mean that when you experience the discomfort of the heat, it takes away your attachment to comfort? One fans oneself because one is hot and would rather be cool. Does the perception of the ultimate truth change that? Is there still some attachment to feeling a certain way? Obviously this isn't something just purely intellectual but has some impact on how we experience the world."

Rinpoche: That is the basic difference between the experience of relative and ultimate truth. If you experience the world relatively, there is fixation and a strong dualistic clinging to attachment and aversion. If one begins to realize the ultimate truth, not just from an intellectual level, then one has less clinging, to the point at which one realizes it fully and experiences no clinging whatsoever.

Next question: "Can one experience the ultimate and relative at the same time?"

Rinpoche: Yes, that's the whole point. Without eradicating the relative truth, the ultimate is realized – this is what the ultimate truth is. For instance, if you read the life story of Buddha Shakyamuni, you will see that the relative truth was so alive in him, at least in the eyes of others he demonstrated the relative truth and experienced it deeply. He didn't experience it because he clung to it, rather to show that the relative truth does not stand in opposition to the ultimate truth. Concerning the ultimate truth, the Buddha is the best example of someone who has realized it.

Next question: "If the ultimate point of view isn't the ultimate, how is it that we ever fall into a state of mind that is ignorant of the ultimate truth?"

Rinpoche: It sounds like a discouraging beginning and an encouraging end. Buddha Shakyamuni spoke about beginningless time and that there is no end. It's a very exciting subject. Ignorance isn't that bad, because we couldn't experience enlightenment if we weren't in samsara, the state of ignorance. So you shouldn't be too negative about ignorance, because it is a matter of the truth of interdependence.

Next question: "If ultimate truth has to be experienced in the relative world, then it sounds like we are still sort of stuck in samsara. Is it just that we don't experience it as samsara? If we can perceive ultimate truth from what I have understood, it has to be in the relative world. And since we do live in a relative world and deal with relative truths all the time, how would we know if we were face-to-face with ultimate truth? And how do we get there?"

Rinpoche: Without having to abandon relative reality, you can experience the ultimate truth. If you try to experience the ultimate truth by stopping relative reality, then it's not ultimate and doesn't have anything to do with the ultimate. Rather, it is an incomplete approach. If you try to experience the ultimate by ignoring and stopping the relative, it is possible to fall into one of the two extremes. The ultimate truth is like a good friend, traditionally described as a mother meeting her lost son. There is a very definite recognition. You need not worry when you face the ultimate truth. It will be very obvious because you finally know yourself after all pretensions have fallen away. When you face yourself, knowing is the easiest thing. The work is getting to that point.

Next question: "I wonder about perceiving. Do we in fact ever perceive ultimate truth? The further point is, it seems to me that we perceive ultimate truth all the time."

Rinpoche: Yes, it is possible. In a Sutra the Buddha said that he never taught anything, but beings perceive. Ultimately, he never taught, but beings perceive the teachings. He perceived that he didn't teach.

Next question: "If the idea arises that I have perceived the ultimate truth, it becomes a commentary, an experience. Do you have any advice on how to deal with that other than just letting go of the commentary?"

Rinpoche: It is not like perceiving it suddenly or out of the blue. It is a gradual process, a blending of situations on subtler levels. As such, it is not a situation that you are suddenly confronted with realization and do not know which language to use. Working with a teacher is very important when it comes to practice and experience. There is a subtlety about it. In the different vehicles we speak about the five paths. One is the path of seeing - one begins to see ultimate truth. The process of seeing is like learning to know a person one sees for the first time. But before this person knows you and you know him or her, you must learn about each other. It is a process.

Next question: "Would you say something about death and grieving as it relates to our clinging, especially of loved ones? Secondly, in the West, we do have a custom of grieving quite a bit and I was just wondering if there would be a way in the practice of meditation to lessen this grief? Sometimes it is quite overwhelming."

Rinpoche: Any clinging is pretty much the same. Going into a state of grief isn't particularly helpful for anybody. Realistically, it is a custom that you are expected to grieve, but practically it doesn't help anyone, not the deceased and not the living. This doesn't mean that one should celebrate, but there is no point in grieving. Regarding your second question, grief is common to all people, not only to Westerners. As human beings, we experience the emotions of sadness, unhappiness, and disappointment when someone close dies. From the Buddhist point of view, it isn't a matter of not caring, rather one tries to see that grieving is not beneficial for those who have died and for the living. In the Buddhist tradition, one awakens more to the truth of impermanence and sees that death is inevitable. This experience is intensified by experiencing others' death. The only meaningful attitude for the deceased and for the living is developing and intensifying a compassionate mind, Bodhicitta, 'the enlightened mind of compassion and loving kindness.'

Next question: "You said in the talk that when one does more practice that things get simpler. Is it that the relative and ultimate truths distil into nothing or that they distil into something? Or is it that one's attachment to something or nothing simply goes away?"

Rinpoche: When one has the correct view that there is no contradiction between the two truths, then the practice accords with the view and has the quality of inseparability of skilful means and wisdom. The wisdom of prajna is wisdom of the ultimate truth and skilful means of upaya is the quality of the relative truth. If you advance in practice, then skilful means is wisdom and wisdom is skilful means; the relative is ultimate and the ultimate is relative. By following the path of practice, one begins to experience a finer balance of ultimate and relative Bodhicitta.

Second Talk

I spoke about the basic principle of the Buddhist view and that one's practice should accord with the correct view. Now I will speak about practice in relation to the view.

The Tibetan term for Sanskrit Buddhist is nang-pa, nang meaning 'home, inward,' so a nang-pa is someone who turns his or her attention inward. A follower of Buddhism can be called 'an insider' and learns to see that the essence of all appearances and experiences is lack of true existence. The nature of the perceiving mind is therefore an important issue for Buddhists. Instead of just having the view of how things are or how they should be, devotees turn their attention inward to experience the relationship between the apprehending mind and appearances in the world. So, in Buddhism it's very important to look inward and to work with one's mind.

Working with one's mind doesn't mean one becomes an introvert, rather one works with one's experiences of the world while focusing on one's mind. It's necessary to integrate one's practice with one's experiencing mind while knowing that all appearances lack true existence. The great yogi and one of the greatest meditators of the Kagyü Lineage is Jetsün Milarepa who stated that he did not know the Buddhadharma that teaches how to tame the mind but that he knew how to tame the mind. He didn't imply that the Buddha didn't teach how to tame one's mind and how to develop an altruistic mind, rather he said that everything points to taming the mind and just talking about it without practicing is of no use. Buddha Shakyamuni taught that all Dharmas concern the mind and appreciating this depends upon one's own propensities and inclinations. And so, because the two truths pervade the mind, one sees that they are inseparable and pervade all things. This means to say that the way one apperceives phenomena depends upon one's mental capacities and experiences. One needs to have the correct view in order to follow the correct path and to stay inspired to continue. It is most important to have the correct view while meditating.

Correct meditation is the second most important factor of practice. Meditation doesn't mean that there is something to meditate on, rather it means becoming accustomed to developing the correct habit, until the practice slowly becomes a habit. Traditionally, meditation practice is taught in the causal vehicle. The practices are calm abiding, which is the cause, and special insight meditation, which is the result. For instance, we are bound in samsara, which doesn't mean that we are trapped in a cage and cannot get out nor that a vicious cycle caught us unaware and makes us lose control. Being caught in samsara means having developed certain habits that are very strong and drive one to lead one's life the way one does. The habit of experiencing samsara is due to clinging to duality and it isn't easy becoming free of this delusory habit. One can't sweep samsara away or just leave it behind, and one can't just step into nirvana, the state free of delusory habits. One needs to develop wholesome habits and become accustomed to them by resorting to virtuous habits instead of non-virtuous habits. There is the saying in Zen Buddhism that one replaces an unpleasant smell with a pleasant one and that the purpose of meditation practice is breaking through one habit by replacing it with another habit. I want you to know that you can develop a good habit as a remedy or antidote to overcome a bad one. The difference between wholesome and unwholesome habits is that the former means being free of expectations, doubts, hopes, and fears.

Calm abiding meditation is related to the relative truth and is practiced so that one attains mental stability and one-pointed concentration. Special insight meditation is related to the ultimate truth, in which case one begins to see the non-conceptual and non-referential nature of one's mind based upon having attained mental stability and one-pointed concentration. It is very difficult to experience special insight without having cultivated a stable mind. Just as the two truths are inseparable, one should not separate calm abiding from special insight meditation practice.

The Tibetan term for special insight is translated as 'seeing more and seeing what is greater.' Seeing greater means one gains a more correct picture of things as they appear and are. One needs to have a calm and stable mind in order to see things more clearly. Having a calm and stable mind sharpens one's perception and makes one more open. For example, the brocade table cloth in front of me is very detailed and fine. Upon first glimpse, it only seems to be coarse, but I see that it is very detailed when I look at it more carefully. Everything is seen vividly and clearly and never as coarse when one has developed special insight. So, it's important to understand that calm abiding and special insight are inseparable.

Questions & Answers

Question: "Your Eminence. I would like to question you further about the inseparability of special insight and calm abiding to the extent that as a practice experience it is not uncommon to have your mind seem to rest without particular concentration and not to be one-pointed, so much so that the mind goes out and hangs out. That can go on for an extended period of time and it doesn't mean that it is an undisciplined practice. It seems to be co-extensive and goes along with discipline. In my understanding, that experience of going out and hanging out or just resting the mind there, special insight and calm abiding seem to just suspend for a while. What am I talking about?"

Rinpoche: That seems to be fine – hanging out without a reference-point and without being distracted. It wouldn't be particularly wrong calling it special insight, but it would be more correct to call it "path-special insight," because special insight is discussed from the point of view of fruition. What we really mean by special insight is experiencing selflessness.

Same student: "I would like to return to the same question in just this sense. Does this not imply then a separation of a special insight experience to a calm abiding experience? In that sense, do they co-exist?"

Rinpoche: In path-special insight there is still a separation taking place in the mind because there is no place to rest the mind, yet there is no distraction, which is the aspect of calm abiding.

Same student: "Would you extend that to the fruition?"

Rinpoche: The nature of all situations is the inseparability of methods and wisdom. At fruition, we speak of skilful means and wisdom. Calm abiding is skilful means and special insight is wisdom.

Same student: "Selflessness and the ability to handle yourself and the world?"

Rinpoche: You could describe it that way when you discuss the inseparability of clarity and emptiness.

Same student: "The experience of clarity and emptiness has not been available to me, consequently to use it as a reference-point is not …"

Rinpoche: Right now it would be good to have some confidence in the inseparability of skilful means and wisdom. As your practice progresses, the realization of the inseparability will begin to become more obvious for you. The practice seems to be going very good - resting but not fixating on a point and being non-distracted.

Next question: "Your Eminence. Could you talk a little bit about exactly what is meant by one-pointedness? What the one point is?"

Rinpoche: Basically it means not being distracted. However, simply being free of distractions is not enough; it's not sufficient. You have to also be free of clinging to the experience of non-distraction.

Same student: "What I was wondering is that it seems to me that a lot of people think that one-pointedness means kind of spatially making your mind into a dot. I was wondering whether one-pointedness didn't have more to do with nowness, just being here now?"

Rinpoche: It depends upon a particular stage of practice as well as upon an individual's capacity. In calm abiding, there is progression from grosser to subtler levels of practice. There is also calm abiding with a reference and without a reference. Essentially, yes, one-pointedness has to do with your understanding. It means being free of the four extreme mental limitations of believing things exist, do not exist, both exist and do not exist, and neither exist nor do not exist, and being free of the eight mental constructs that phenomena have such attributes as arising and ceasing, being singular or plural, coming and going, and being the same or different.

Same student: "Could you say that the relationship between calm abiding and special insight … What comes to mind is dropping a stone into a pool of water. There is a place where it hits and there are the ripples that go out, so that the center seems to be there and being there it is awareness that can expand. So, it includes the presence, but then it isn't enough. There has to be the expansion. So, special insight is bigger than calm abiding but starts from it like that."

Rinpoche: When one experiences one-pointedness through calm abiding, it is the experience of one's mind free of distraction. Out of that one experiences special insight or selflessness. From the Hinayana point of view, it is selflessness. From the Mahayana point of view, it is the truth of Dharmata, 'suchness.' When you experience emptiness, you are free of any notions or concepts of expanding or lacking expansion.

Next question: "Your Eminence. You spoke about developing the habit of meditation as an antidote to samsaric habits. A lot of us develop the habit of calm abiding meditation and then we develop new habits of the Ngöndro and Sadhana practices and get out of the habit of calm abiding meditation. Do you think this is a problem?"

Rinpoche: No. There is not only no problem, but it is exactly what brings about a balance. If we understand the path correctly – that our view and the path must be free of the two extremes -, then through calm abiding practice one begins to become free of the view of eternalism. Again, because of one's past history of habits, one might develop similar habits while practicing calm abiding, which could take one to the other extreme of believing in nihilism. It is through the practice of Mahayana and the preliminaries that one becomes free of falling into the belief of nihilism. Then one is on the Middle Path.

Next question: "Do you think that doing too much calm abiding practice could be dangerous?"

Rinpoche: If you cling to it, yes.

Same student: "What about nostalgia for it?"

Rinpoche: That is clinging, so you must have a great time with calm abiding. Frankly, we are Mahayana practitioners and need to remember the path and be free of the two extremes. It is important to keep this in mind. Also, any practice you do needs to combine calm abiding and special insight. Visualization practices are calm abiding. If you don't do the visualizations and don't pay attention, then your Ngöndro practice will be faulty.

Next question: "When you speak of seeing and special insight, it's clear that you mean something beyond visual seeing. And I wonder if you could say more about what is being seen and who or what faculties are seeing? In what sense does the seeing occur?"

Rinpoche: Actually, it is an interesting use of words. The Tibetan term translates as 'exceptional seeing,' but it really means seeing what isn't seen. There isn't anything to see or anybody seeing anything.

Next question: "In relation to the question about one-pointedness. You said it means having no distractions. I am wondering, distraction from what?"

Rinpoche: It would be more precise to say freedom from expectations and doubts, because distractions take place due to hopes and fears. For instance, there is clinging to the wish that things truly exist.

Same student: "So, if I am sitting and become distracted by the trees outside, that is because I … It seems like …"

Rinpoche: Yes, the tree does not come to you to distract you, but you hope that it is a tree and therefore you aren't comfortable.

Same student: "Discomfort, but I like looking at the tree."

Rinpoche: Then you should leave the sitting practice. You do not think that the two go together very well.

Next question: "Your Eminence. I have a question about the use of the term 'insider' in terms of a Dharma practitioner. Let me give a scenario: If one practices calm abiding and special insight arises as an experience, there is a particular brightness of color, a particular poignancy of sound, in fact, phenomena speak to one as if they were one's teacher somehow without distraction. It isn't a question then of inside or outside, or is it?"

Rinpoche: All displays of the phenomenal world are manifestations of one's mind. The outer play of phenomena is a manifestation of the inner mind, which is communicated through speech. Inside there are certain belief systems, e.g., believing that external phenomena are real, that they exist of their own accord, and so forth. That is the main point the mind focuses on. We pay attention to what creates the situations for manifestations to appear. There are different glimpses that are appropriate, others are sidetracks. Things take place due to inter-dependence. The inter-action of outer situations and the inner mind produces the result, which is neither outside nor inside.

Next question: "I have a question about how one habit is replaced by another. Is it possible to be in a state of no habit?"

Rinpoche: Yes. First there must be a balance, though. Right now, there is no balance and one side is stronger than the other, so one develops a specific good habit to outweigh the confused habit. One must reach a point of balance. Then one can advance to the possibility of becoming free of habits.

Same student: "From then on means when the wholesome habits become stronger than the negative ones?"

Rinpoche: Not stronger but balanced. Generally, when one talks about having accumulated great virtue, wholesome habits are stronger than unwholesome habits. The real meaning is that the two should be balanced and then there is the possibility of experiencing freedom from habits.

Next question: "What about the process of selecting bad habits?"

Rinpoche: There must be a misunderstanding. There aren't any bad habits that you can brush aside, rather balance refers to the fact that you don't favour either negative or positive habits.

Same student: "Let's say you get the habit of having a drink after work everyday. Then you get into the habit of meditating instead of having a drink. Are you saying that the proper balance is to some days …"

Rinpoche: No. Let's say that drinking is a bad habit and meditating is a good habit. What I mean is that one doesn't rely on meditation to overcome drinking for the rest of one's life, because then there wouldn't be much point in relying on meditation to give up drinking after one has. What I mean to say is that one does not rely on meditation and at some point does not think that not drinking is a big deal.

Same student: "Is it a matter of indifference?"

Rinpoche: Being free of habits means being free of good and bad habits.

Third Talk

In the last talk I spoke about mediation practice according to Hinayana and now I wish to speak about meditation practice according to Mahayana.

While on the path of Mahayana, it's important not to become sidetracked or to fall into the extreme of samsara or the extreme experience of personal peace, which is nirvana of Hinayana. Disciples of Hinayana practice cultivating a gentle mind through calm abiding meditation and also develop special insight meditation. Disciples of Mahayana furthermore cultivate skilful means of Bodhicitta that prevents them from falling into any extreme.

Relatively, cultivating Bodhicitta means wishing to benefit everyone by developing a mind of loving kindness and compassion. It is the means to develop genuine and altruistic openness toward all living beings. Ultimate Bodhicitta is called "co-emergent wisdom" in the Tantras and means realization of the inseparability of the wisdom of emptiness and the skilful means of compassion, attained by practicing the two aspects of relative Bodhicitta, which are aspiration and application. The analogies for the aspects of Bodhicitta are wishing to go and actually going. A particular practice that devotees engage in to develop Bodhicitta of aspiration that is an all-embracing intention to benefit all living beings without exception is contemplating the Four Immeasurables. They are: immeasurable loving kindness, immeasurable compassion, immeasurable joy, and immeasurable equanimity. Devotees develop Bodhicitta of application by engaging in the practices of a Bodhisattva, which is the way of the Victorious One's sons and daughters.

The practices of a Bodhisattva are called paramita in Sanskrit and are perfections. The term paramita is translated into Tibetan as pha-rol-tu-phyin-pa, which literally means 'reaching the other shore.' Therefore the six paramitas, which are generosity, discipline, patience, perseverance, meditation, and wisdom-awareness, do not refer to qualities we usually have in mind when hearing these terms. Being generous is certainly honourable and praiseworthy, but it isn't a perfection until a disciple has gone beyond dualistic notions and is free of the concepts regarding a subject, object, and an act of giving while performing generous acts. Continuing to take generosity as an example for the proceeding four paramitas, it is a perfection when it is performed with realization of the sixth paramita.

Cultivating Bodhicitta is the root and source of all practices of a Bodhisattva. Hinayana may not stress Bodhicitta as is the case in Mahayana, nevertheless it is included in their practices, too, because selflessness cannot be experienced in the absence of Bodhicitta. It is a central practice in Mahayana, all the more so in Vajrayana. No matter how profound a practice might be, it is of little use without Bodhicitta - the king of all practices.

Questions & Answers

Question: "Your Eminence. If you would correct my understanding. In any given situation or as phenomena appear to arise, we can have essentially one or two relationships, one being open and friendly, as you say, and the other being closed. It seems to me that as we were discussing non-distraction in calm abiding that the non-distraction is a commitment to that openness and that is in a sense the perfection of moral discipline or ethics. That is the one-pointedness, the allegiance, rather than particular actions. From there that openness gives birth to wisdom-awareness. Rather than a creation of those things, one thing tends to give birth to the next. So, from wisdom-awareness there is space for equanimity, and equanimity gives the richness for generosity, and generosity gives the impulse for action. The question is, am I mistaken in some place there?"

Rinpoche: I didn't realize that I had made it so complicating. Basically, it sounds like there are things one can put together in that the correct practice of calm abiding has a very generous quality about it. When one has a calm and gentle mind, then stability is an expression of discipline. When one has a gentle mind, then mind's greater simplicity makes wisdom-awareness possible. There is definitely a relationship and one can develop wisdom-awareness through calm abiding practice. One can practice generosity and the other paramitas more intelligently when one has wisdom-awareness, but it isn't necessarily the case that they arise from wisdom-awareness. One has to practice the paramitas, like generosity, more correctly.

Next question: "Your Eminence. Many of us are first generation practitioners of the Buddhadharma here in No. America. You have students in the East and in the West. Could you tell us if there are any particular difficulties that are characteristics of Western students that you might be aware of?"

Rinpoche: From my personal experience, students of the Buddhadharma in the East and West have a certain amount of sincerity and aspire to pursue the path to the best of their ability. I am very happy with all practitioners, it doesn't matter who or where they are, which cultural background they come from, or whichever kind of neurosis they have. As long as one is neurotic, the expression is the same. I have seen that there are certain shortcomings. In the East, more people base their practice on blind faith; in the West, people have constant doubts that return again and again. I think it would be very good if the two would merge and students would exchange experiences. I am very impressed with the older Dharma students in the West. I like working with them very much.

Next question: "On the level of relative Bodhicitta, it seems that aspiration is easier than application, that one can actually have the genuine aspiration to be generous but still gets involved with personal likes and dislikes, personal irritations and impatience. Apart from the contemplation of the Four Immeasurables, are there any other practical tips you can give us on how to work further with application?"

Rinpoche: It is necessary to develop genuine aspiration. Yes, there is a procedure to develop aspiration and application. Whether one can practice Bodhicitta of application correctly depends upon having genuine and sincere aspiration, as illustrated in the example of having a definite intention to go moves one to actually go. The mind is the leader and the body is its servant that follows mind's intentions and desires. So, it is necessary to give rise to genuine aspiration so that one can smoothly practice Bodhicitta of application. Giving and taking is a good practice to open oneself to others and to be of service to them; it is the practice of Bodhicitta of application.

Next question: "Following up with the question about the doubts we have, sometimes from my own experience when acting out of what seems to be generosity, I later realize there is a subtle self-interest in doing something that I thought was quite generous at the time. I am wondering whether that is simply the way to learn or whether one can catch that earlier, before acting?"

Rinpoche: It sounds like you are doing well. Certainly, one learns from one's mistakes and refines one's actions more and more. You have done what benefits others and practiced generosity. You see that there might be self-interest. If the self-interest benefited you as well as others, you can see it as self-interest that is fine. If you are aware that it is only self-interest, you can correct it.

Next question: "You spoke about good and bad habits being balanced. My question is about the six perfections. Are they good habits that balance the bad ones, that one shouldn't have too much of some, or is there something more?"

Rinpoche: There must be some confusion due to circumstances. Generosity means continuing to practice generosity and benefitting others with the correct motivation, thus accumulating virtue. But generosity alone will not bring enlightenment. For it to be a perfection, it must be united with wisdom of emptiness and compassion. Practicing generosity without being free of the idea that there is someone giving something to someone is having another habit, which isn't really wholesome.

Next question: "I am wondering about the process of discovering restful mind. In other traditions that I tried, there was a lot of emphasis on concentration as a way of using it as a catalyst that provides some kind of awareness. I am wondering why in this tradition concentration seems to be played down?"

Rinpoche: Yes, there is a need for concentration in the way of paying attention and being mindful. But, merely paying attention and being concentrated can narrow one down. If one concentrates too much, the concentration spins things around, like a spinning-wheel, and things become more twisted. So when paying attention, it's important not to hold on to something and then there is spaciousness and openness.

Next question: "Your Eminence. Do you think that as laypeople there is an obstacle for us in developing ultimate Bodhicitta, because we will always tend to want more of the Four Immeasurables for our children and loved ones? Or do you think, in fact, that it teaches us ultimate Bodhicitta?"

Rinpoche: It isn't necessarily so. If one is living the life of renunciation by giving up a householder's life and generates Bodhicitta correctly, then this life will be easier and one would have more time and energy for practice. Then the practice would be more effective. This is why there is the practice of discipline, why the Buddha placed a great deal of emphasis on the Sangha of ordained monks and nuns. But the main thing is Bodhicitta. Being an ordained member of the Sangha doesn't mean one has more Bodhicitta than others. It depends upon the individual. Some people have problems being a householder, others don't.

Next question: "Your Eminence. In Mahayana it seems that we welcome aggression and it helps us develop Bodhicitta in our practice of giving and taking. Passion, the same way, helps us. But, what is the antidote for ignorance and how do we work with it in Mahayana?"

Rinpoche: The antidote for ignorance is developing wisdom-awareness. If you are really developing Bodhicitta then it shows that you have wisdom-awareness. Responding with Bodhicitta in the face of aggression shows that it comes from wisdom-awareness.

Next question: "Your Eminence. You have used the expression accumulating merit or virtue and I have seen it a lot of times in the chants. But I don't really understand it and I don't know why I would accumulate merit or what I would do with it."

Rinpoche: Accumulating merit doesn't mean you collect something that you stack into a heap and in the end don't have enough room to store the things you have gathered. If this were the case, we would have enormous difficulties finding enough room to store all our defilements. Accumulating merit means giving up destructive habits; furthermore, it means developing worldly and spiritual habits that benefit oneself and others. We speak about the two accumulations of merit and wisdom. Simply being generous, for example, doesn't mean one has transcended habits, though. So it's necessary to accumulate wisdom.

Thank you very much.

Dedication

Through this goodness may omniscience be attained

And thereby may every enemy (mental defilement) be overcome.

May beings be liberated from the ocean of samsara

That is troubled by waves of birth, old age, sickness, and death.

By this virtue may I quickly attain the state of Guru Buddha and then

Lead every being without exception to that very state!

May precious and supreme Bodhicitta that has not been generated now be so

And may precious Bodhicitta that has already been never decline, but continuously increase!

Long-life Prayer for His Eminence the Fourth Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche,

Lodrö Chökyi Nyima

May the life of the Glorious Lama remain steadfast and firm.

May peace and happiness fully arise for beings as limitless in number as space is vast in extent.

Having accumulated merit and purified negativities,

May I and all living beings without exception swiftly establish the levels and grounds of Buddhahood.

The instructions were presented at Karma Chöling, Vermont in 1985 and translated from Tibetan into English by Ngodrub Burkhar, transcribed in 1986 & edited again for the archives of Pullahari Monastery in 2009 by Gaby Hollmann from Munich, responsible for all mistakes. The group photo with Rinpoche was taken at the Dharma Center at Huy, Belgium in April, 1991. This article is copyright of the Jamgon Kongtrul Labrang at the Great Pullahari Monastery in Nepal, 2009. All rights reserved.