Patience

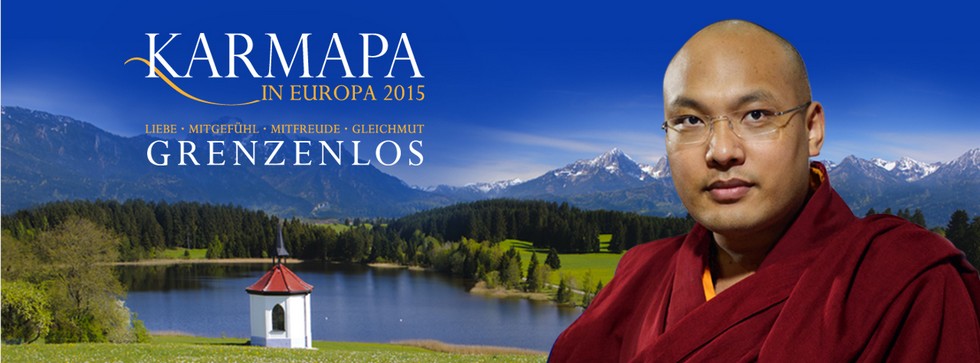

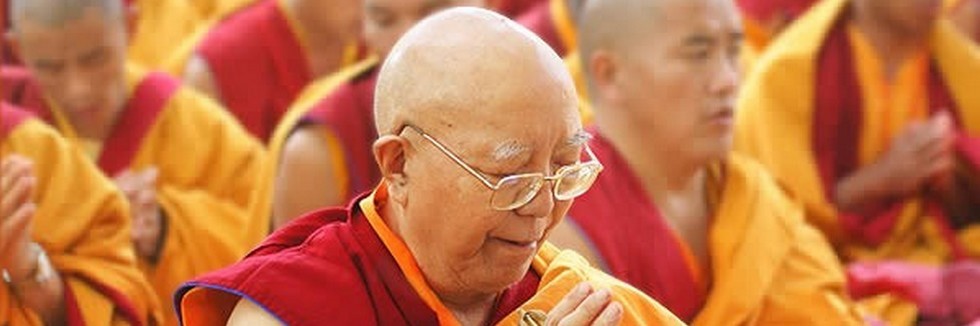

His Holiness Gyalwa Karmapa & Venerable Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

at the Vajra Vidya Institute, Varanasi. India, in 2008 (or 2009).

Venerable Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

Patience – bZöd-pa

Instructions on Chapter 6 from the

Bodhicharyavatara - The Way of the Bodhisattva,

Composed by Shantideva

Translated by David Karma Chöphel

When we are practicing or listening to the Dharma, then we need to develop the motivation of Bodhicitta. All of you have come here out of faith and devotion to the Dharma, so it’s certain that you will have this really good motivation. But we are all ordinary individuals. We might have a good heart, but sometimes we might forget it or we might just remember it slightly. That is why all great masters and great scholars of the past have said that we need to develop the motivation of Bodhicitta; we need to have this pure motivation. This is the tradition of great masters saying that we need to develop this.

Now if this happens in an unforced and spontaneous way, that we naturally have the good motivation to help all sentient beings, then it is wonderful, it is great. But sometimes we have to force it a little bit. We have to think, “I need to listen to the Dharma for the benefit of all sentient beings. If I do this, it will be very good.” So we sort of fake it, we alter our motivation a little bit, and as we do that, we will gradually come to have a real benefit. So, for this reason, please think that you are receiving these Dharma teachings in order to benefit yourself and all sentient beings.

The Way of the Bodhisattva by Shantideva presents the teachings on the six paramitas in order. With the first of these, the paramita of generosity, there’s not a particular chapter that is devoted to generosity, but generally, when we talk about generosity, there are two types: making offerings up to the Three Jewels and making gifts down to those who are suffering and in need, the down-trodden. The first of these is covered in the second chapter, which teaches us about making actual offerings and making mental offerings. The other type of offering, giving to the down-trodden, has three types. There is giving material things, giving Dharma, and giving freedom from fear. For giving material things, there are three types of giving: there is just giving, great giving, and then there is the giving that is difficult to do. The giving that is difficult to do is giving the gift of parts of the body and things like that, which is described in the instructions on mind training. Then in The Way of the Bodhisattva there are three chapters – the chapters of mindfulness, vigilance, and carefulness –, and in these three chapters the paramita of transcendent discipline is taught. Following that there are chapters for each of the next four transcendences – the transcendence of patience, the transcendence of diligence, the transcendence of meditation, and the transcendence of wisdom; so each of these has their own chapter.

We have eight sessions during these teachings and during these eight sessions I thought that I would spend the first two discussing the chapter on patience and then six sessions on the chapter on meditation. The reason for starting out with the chapter on patience is that we are all ordinary individuals and therefore often have difficulties on account of the afflictions and disturbing emotions. In particular, we have difficulties because of anger. People often ask me in interviews, “What should I do? I have anger. How do I get rid of my anger?” I hear many questions about this and often don’t have anything to say. The instructions given in the chapter on patience in The Way of the Bodisattva are very helpful for this.

Generally, when we experience anger, there are two different types of remedies that we can use for anger and hatred. The first of these remedies is the wisdom that realizes selflessness. This might be realizing the selflessness of phenomena or it might be realizing Mahamudra through the methods of the secret Vajrayana. If we can do this – this comes from wonderful experience and realization -, it allows us to give up all the afflictions that need to be abandoned. This is a way to abandon them completely, to uproot and eradicate them completely. But it’s something that is difficult for us ordinary individuals to do. It’s hard for ordinary individuals to immediately eradicate all the afflictions. In order to do so we need to develop the wisdom that sees the truth of the path of seeing. Upon seeing, we can give up what needs to be given up and then gradually develop the wisdom of the path of meditation and meditate upon that. But developing the wisdom of the path of seeing and then developing the wisdom of the path of meditation and meditating upon this is not all that easy for ordinary individuals to do. So, in The Way of the Bodhisattva, it teaches a way for ordinary individuals to deal with their afflictions, overcoming and stopping them. This way we can decrease our afflictions.

In particular, we need to decrease and overcome the afflictions of hatred and anger. What is the way to do this? Well, we have imprints from being in samsara since beginningless time, and because there are these imprints within our mind streams, occasionally we have hatred and anger that become manifest. When those become manifest, we will say nasty things and we will do bad and wrong things with our body. When this happens, is there anything we can do about it? Well, taking medicine won’t to help. There’s no other method that will help, but there is a way. If we realize the defects of anger and the problems that anger causes, then we find that we will be able to apply the antidotes.

The temporary antidote for hatred is to contemplate and practice patience. If we just say, “I’m going to be patient,” are we going to be patient? It’s not going to happen like that. First we need to think about the benefits of being patient, about the qualities of patience, and then we will develop interest in it. Through having interest, we will develop faith in the benefits and then we will think that we really need to develop patience in ourselves. With that pure and wonderful motivation, we will be able to realize the defects of hatred and anger and the benefits of patience. Then, gradually, this will help us; we won’t get angry as much and we won’t feel as much hatred. But if it does happen, if we do feel anger, then we will be able to apply the antidote. For that reason we think about and practice patience.

But thinking about patience will not eradicate our anger. It is having a real, pure motivation, seeing the faults of hatred and the afflictions, and thinking about the reasons why we need to not get angry, the benefits of that, and recognizing that, and then practicing that. Through gradually doing that we will be able to decrease the affliction of hatred. For this reason, in the short term it’s extremely beneficial.

Often we think to ourselves, “Anger is no good. Hatred is no good,” but we need to really think about just what are the defects of anger. We need to really know them in detail, to understand them thoroughly. We need to understand how it is that hatred and anger harm us, how it is that they cause us difficulties and problems. Actually, some people think, “Well, anger is not all that bad. It’s like a real hero, a brave person. I can really get things done with it.” They think of it as being like a quality, that the afflictions of hatred and anger are really good, that they help them get things done. They think that if they try to do things in a nice way, sometimes they don’t get anywhere, but if they just go in there and get angry and fight and struggle, then they can really get things done. So they think of hatred and anger as being a quality. But if we think of hatred and anger as being a quality, then that makes an obstacle to actually giving it up. For this reason, the faults of anger are taught here.

First it teaches the problems of anger in terms of the karmic results, So, here there are two different types of faults with anger. There are the unseen faults and there are the seen faults, the faults that are visible in this life. The unseen faults are how it is such bad karma, a bad action, how it is a very strong and bad misdeed. So, in this life, if we have a lot of anger, we will not have any happiness. But also we will not have any happiness in future lives. About the unseen faults of anger, the first verse of the chapter on patience in Shantideva’s text says:

All the good works gathered in a thousand ages,

Such as deeds of generosity

And offerings to the Blissful Ones –

A single flash of anger shatters them.

So, anger is a really strong misdeed and wrong-doing. If we have very strong anger, then it can destroy a lot of the good that we have done. For instance, if we have a very strong amount of hatred, such as the anger that would motivate us to draw blood from a Buddha, then this can have really strong karmic consequences. That’s a very big misdeed, a very big non-virtue. There are many different misdeeds other than anger, but there’s none that is similar to anger.

No evil is there similar to anger,

No austerity to be compared with patience.

Steep yourself therefore in patience,

In various ways, insistently.

But does this mean that we have no chance to attain liberation and freedom for ourselves if we have no anger? No, it doesn’t mean that. There’s an antidote for anger, and that antidote is patience. There’s no austerity like patience. If we practice patience, then we won’t feel angry and then we’ll also not experience the karmic ripening of that anger. So it’s important that we don’t lose ourselves to anger and that we are able to practice patience. So, this is pointing out the karmic benefits and karmic results of contemplating and practicing patience. That is the unseen karmic result.

Then there are the results of anger that we see in this life. The stanza says:

Those tormented by the pain of anger,

Never know tranquillity of mind.

Strangers they will be to every pleasure;

They will neither sleep nor feel secure.

When we get angry, a lot of it is really like a sickness, like an illness and pain. So if we have anger in our lives, then we will have no happiness of mind, and because we have no happiness of mind, we will also have no comfort and health in our bodies. Also, when we get angry at night, we won’t be able to sleep at night. So this is showing how anger and hatred create problems and sufferings for ourselves; but they also create pain and suffering for others.

Even those dependent on their lord

For gracious gifts of honors and of wealth

Will rise against and slay

A master who is filled with wrath and hatred.

His family and friends he grieves,

And is not served by those his gifts attract.

No one is there, all in all,

Who, being angry, lives at ease.

If we are angry all the time, then we may have friends and family, but we are always fighting and getting into problems with them. As a result, we do bad things with our body, we give them a hard time, and we say harsh words. Finally, in the end, even our friends and family will be upset with us. They will be hurt by it – they will not like it at all. Also, “… and is not served by those whose gifts attract.” Most people give gifts and people like it. If you are always angry, even if you give gifts, people will take the gifts, but they won’t be happy about it; they won’t like you and they won’t enjoy it. There won’t be any happiness or joy at all. In general, there is just no joy or happiness to anger. It says, “No one is there, all in all, who, being angry, lives at ease.”

All these ills are brought about by wrath,

Our sorrow-bearing enemy.

But those who seize and crush their anger down

Will find their joy in this and future lives.

If we get angry, then we won’t be happy and we won’t make others happy. We will not bring ourselves temporary or ultimate happiness. If we know that because of anger and hatred we will have no happiness, then when anger and hatred actually happen, we will realize, “Oh, this is going to cause problems. I’m not going to allow myself to get angry. I’m going to put this anger aside and not act upon it.” It will help us in this way. Also, if we keep the teachings in mind all the time and think, “I’m not going to allow myself to get angry. I’m not going to act on what usually causes me to get angry,” in this way, it will gradually help us not to get angry. So that is teaching the faults of anger and how we can diminish and overcome our anger by knowing this. The teachings on patience follow.

First we need to think about how anger happens. We need to ask, “What is the object that we get angry at?” The great masters of the past said that actually there are nine different bases for feeling enmity or discontent. These are, first, when we think, “That person is hurting me now,” which is thinking in the present. Then there is thinking about the past, “That person hurt me in the past,” or about the future, “That person is going to hurt me in the future.” Those are the three grounds – being hurt now, in the past, or in the future. Then there is thinking about others, “They are hurting my friends, they are hurting my family,” which is thinking about the present, or “They hurt my friends and family in the past,” or “They are going to hurt my friends and family in the future.” Those are three. Then we look at our enemies and think, “They are helping my enemies,” or “They helped my enemies in the past,” or “They will help my enemies.” Another three. All in all, these are the nine grounds for malcontent. When talking about anger, it usually arises on one of those nine grounds. But if we look and actually think about it, we can cause harm to ourselves, to our friends, and to our enemies. We can take these nine grounds for malcontent and condense them into three different grounds for getting angry.

11. Pain, humiliation, insults, or rebukes –

We do not want them

Either for ourselves or for those we love.

For those we do not like, it’s the reverse.

The first of these is when we have been harmed ourselves, we think someone is going to harm us, or they are hurting us now. When this happens, we should make sure that we don’t allow ourselves to get angry and need to practice patience instead.

When we practice patience, there are three different types of patience: there is patience with pain and suffering, patience regarding the Dharma, and patience of not thinking at all about enmity or malice.

We get angry when we think someone is hurting us. It will be really hard to develop patience while thinking, “This person is causing the problem. This is the problem. I’m suffering. I’m having a hard time.” We do experience suffering, difficulties, and problems, but actually these sufferings and problems are really not that bad. This is taught in the 12th stanza:

12. The cause of happiness is rare,

And many are the seeds of suffering.

But if I have no pain, I’ll never long for freedom.

Therefore, O my mind, be steadfast.

It’s really difficult to find the causes of happiness, but the causes of suffering and pain come up very quickly and all the time. Is suffering really bad? Is it always a problem for us? No, because feeling suffering helps us give rise to renunciation for samsara; it helps us to feel faith in the Dharma and to believe in the Three Jewels. Sometimes suffering is a problem, but if we never experience it, then we’ll never long for freedom. If we see difficulties and problems like this, we can have the benefit, and for that reason we need to practice patience.

People go through many difficulties. The 13th stanza presents an example:

13. The Karna folk and those devoted to the goddess,

Endure the meaningless austerities

Of being cut and burned.

So why am I so timid on the path of freedom?

This refers to ancient traditions in India, where people practiced austerities by sitting in the middle of a fire and sweating it out, or they cut or burned themselves in various places of their bodies. They underwent all these sufferings and problems, but there’s no benefit to that. If we practice patience with suffering, difficulties, problems, and harms that our enemies inflict on us, then this can become the cause for us to attain freedom and the ultimate result. So, we need to practice being patient.

The fourteenth stanza teaches how sometimes we think that patience isn’t easy, e.g., “I can’t bear the pain in my body.” It doesn’t seem easy at first, but we can become used to it, as stated in the 14th stanza:

14. There’s nothing that does not grow light

Through habit and familiarity,

Putting up with little cares,

I’ll train myself to bear with great adversity.

So, if we just get used to it, if we grow accustomed and familiar with it, then something can seem to be difficult at first, but as we get used to it, then it can grow easier and easier. To begin with, we start out with small pains and difficulties and grow used to them. As we get used to them, we can bear larger and larger problems, until eventually we will be able to withstand and be patient with great difficulties. We need to develop this kind of patience.

15. Don’t I see that this is so with common irritations,

Bites and stings of snakes and flies,

Experiences of hunger and thirst,

And painful rashes on my skin?

Sometimes there are little things, “common irritations.” We can start with them, and then:

16. Heat and cold, the wind and rain,

Sickness, prison, beatings –

I’ll not fret about such things.

To do so only aggravates my trouble.

Sometimes it’s hot, there’s rain or wind, or we get sick. There are many sorts of problems. When they happen and we think, “I can’t bear it,” and become discouraged and distraught, our suffering will increase. But if we gradually practice patience with those difficulties, then we will be able to bear them. This is the benefit of developing patience.

17. There are some whose bravery increases

At the sight of their own blood,

While some lose all their strength and faint

When it’s another’s blood they see.

Developing patience depends upon our mind. The next stanza says:

18. This results from how the mind is set,

In steadfastness or cowardice.

And so I’ll not scorn any injury,

And hardships I will disregard.

We need to be patient with suffering, difficulties, and problems that we experience. Sometimes it isn’t easy and it seems like we will become discouraged. Since we need to give up the afflictions, we should make sure that we aren’t discouraged. Giving up the afflictions is like fighting a battle with them.

19. When sorrows fall upon the wise,

Their minds should be serene and undisturbed.

For in their war against defiled emotions

Many are the hardships, as in every battle.

So, we need to struggle against the afflictions, in particular against our anger. Is this difficult? Of course, sometimes we have difficulties. Fighting with our anger is how to get rid of our enemies. If we are able to destroy our real enemy, which is anger, then it will be really helpful. We will feel good if we aren’t overcome by our anger and can think to ourselves, “I didn’t get angry. I was able to diminish my anger.”

Thinking scorn of every pain,

And vanquishing such foes as hatred:

These are exploits of victorious warriors.

The rest is slaying what is dead already.

If we are victorious in the battle over our anger, then that’s what is meant by being a hero. We normally think of a hero as being somebody who goes out, fights, and kills enemies in a battle. But that isn’t the real hero; it’s just like shooting at a corpse, i.e., “The rest is slaying what is dead already.” The reason it’s just like killing a corpse is that at some point the enemy will die anyway, so killing him or her doesn’t help. But if we can be victorious in the battle of fighting our anger and if we win, then that’s being a true hero.

The next stanza teaches that even though there is pain, difficulties, sufferings, there is actually a purpose and benefit to them. It says:

Suffering also has its worth.

Through sorrow, pride is driven out

And pity felt for those who wander in samsara;

Evil is avoided and goodness seems delightful.

When suffering happens, we feel upset and disappointed. It’s difficult, but it also has great benefits. We will only become free from samsara if we are weary of it. If not, we will be proud and won’t be able to recognize the difficulties that others also face. As a result, we won’t develop compassion. So, in this way, difficulties and problems are beneficial. Suffering is beneficial; it us to decrease our pride and to develop weariness of samsara. Then our mind becomes tranquil and we can see that not only we feel suffering, but others also feel suffering, and we have compassion for them. Pitying ourselves and having compassion for those who wander in samsara actually help us – it turns out well. By refraining from doing bad things also helps us in future lives. If we understand the difficulties of suffering, we realize that they come from misdeeds. We think, “I’m not going to allow myself to do that.” Avoiding doing bad things will bring benefit in the future. Also, goodness becomes delight. We feel happy about doing virtuous things and unhappy about doing bad things. If we don’t experience any difficulties and aren’t weary of samsara, we won’t feel any particular joy about good things. We won’t feel the need to get rid of misdeeds and non-virtue, and then we do them, which will turn our badly for us.

Of the three types of patience, I have been talking about the patience of recognizing the Dharma. This is seeing that we have difficulties and problems, but this is just the nature of samsara. It’s the characteristic of samsara that everything happens interdependently. So, when others hurt us, we understand that it comes out of circumstances. This second type of patience is taught starting with the 22nd stanza.

I’m not angry with my bile and other humors –

Fertile source of suffering and pain.

So why should living beings give offence?

They likewise are impelled by circumstance.

We get sick and suffer, but we don’t get angry at the causes of our suffering. Since we have an enemy, the stanza says, “So why should living beings give offence?” If there are enemies, we get really angry at them, but what’s the difference? There’s no real difference, because everything happens due to interdependence. When somebody gets angry at us, that person has no control, so we should be able to be patient and not be angry with them.

Although they are unlooked for, undesired,

These ills afflict us all the same.

And likewise, though unwanted and unsought,

Defilements nonetheless insistently arise.

Even though we don’t want to get sick and don’t enjoy it, we will get sick and will have to put up with it. Likewise, “… though unwanted and unsought, defilements nonetheless insistently arise.” So, an enemy means thinking, “I want to get angry.” Nobody enjoys and likes that, but they still do it. There’s nothing they can do about it, so why should we get angry about nothing that can be done?

Never thinking, “Now I will be angry,”

People are impulsively caught up in anger.

Irritation likewise comes,

Though never planned, it is experienced.

People are impulsively caught up in anger. Irritations, that are never planned, also come with pain. In this way:

All the defilements of whatever kind,

The whole variety of evil deeds,

Are brought about by circumstances.

None is independent, none autonomous.

All the misdeeds and all the problems happen because of interdependence.

Once assembled, conditions have no thought

That they will now give rise to some result.

Nor does that which is engendered

Think that it has been produced.

For this reason, there’s nothing we should get angry about. Everything comes up because of interdependence.

The 27th through 30th stanzas speak about the view:

The primal substance, as they say,

And that which has been called the self,

Do not arise designedly

And do not think, “I will become.”

For that which is not born does not exist,

So what could want to come to be?

And permanently drawn toward its object,

It can never cease from being so.

Indeed, this self, if permanent,

Is certainly inert like space itself.

And should it meet with other factors,

How could they affect it, since it is unchanging?

If, when conditioned to act on it, it stays just as it was before,

What influence have these conditions had?

They say that these are agents of the self,

But what connection could there be between them?

Our Buddhist view is that everything happens due to circumstances and because of other conditions, i.e., everything is dependent on everything else. Therefore there’s no reason to get angry at anything in the short term. There are other religions that teach about a permanent self, but this primarily refers to the non-Buddhist traditions, the Samkhya and Vedic religions. For example, they say that there is an autonomous and independent self that has a power and autonomy to bring about its own happiness. I won’t explain these stanzas now, but will continue with the next one.

All things, then, depend on other things,

And these likewise are dependent; they aren’t independent.

Knowing this, we will not be annoyed

About things that are like magical appearances.

This stanza says that all things depend on other things, that nothing is independent, and therefore there’s no reason to get angry at anything. Things are like the illusions of magical appearances that are made by magicians. So, there’s no need to get angry at them.

That has been a discussion of the second of the three types of patience, the first being the patience of putting up with suffering, the second being the patience of recognizing Dharma. Now we have come to the third type of patience, that of not thinking anything about harm done to us. It’s very important to have this kind of patience when people hurt us. We need to think about it well and realize why people hurt us. Then we will be able to practice patience. This is taught in the 37th stanza:

37. When affliction seizes them,

They even slay themselves, the selves they love so much.

So how can they not be the cause

Of others’ physical distress?

Sometimes people have really strong afflictions. For ordinary beings, they are so strong that they even hurt themselves, the selves that they cherish so much. Although people cherish themselves the most, sometimes they are filled with so much anger and hatred that they lose all control, thus they fall under the power of their afflictions and even commit suicide. If they can’t prevent themselves from hurting what they love the most, how can they prevent themselves from hurting others? Instead of thinking, “They are hurting me,” we should think, “It’s not their fault. They have no control over themselves, so I need to be patient with them.”

38. Although we almost never feel compassion

For those who through defilements

Bring about their own perdition,

What purpose does our anger serve?

We need to feel compassion for those who are hurting us and think, “Since they have no control over their afflictions, it’s not their fault. Their afflictions are so strong they could even kill themselves or hurt me. I shouldn’t get angry at them for having no control over their afflictions, which is a characteristic of ordinary beings. I should feel compassion for them.”

39. If those who are like wanton children

Are by nature prone to injure others,

There’s no reason for our rage,

Which is like resenting fire for being hot.

People normally cherish themselves the most and therefore hurt others a little bit. This is just the nature of how people are, so why get angry at them? For example, fire is by nature hot, so it’s not the fire’s fault if we get burned; there’s no point in getting angry at the fire. In the same way for ordinary sentient beings. It’s their nature to occasionally hurt others, so why get angry?

40. And if their faults are fleeting and contingent,

If living beings are by nature mild,

It’s likewise senseless to resent them –

Just like it’s senseless being angry at the sky when it’s full of smoke.

Generally, people only get annoyed and angry sometimes. Most of the time they are nice, gentle, and kind - that’s the way they are. They get a little bit angry and hurt others occasionally, but there’s no point in getting angry at them. For example, it’s foolish getting angry at the sky because of a little bit of pollution. It’s the same with ordinary sentient beings. Most of the time they are nice, so it’s foolish getting angry at them if they annoy us and are mischievous once in a while.

41. Although it’s their sticks that hurt me,

I’m angry at the ones who wield them, striking me.

They are driven by their anger and hatred,

Therefore I should take offence with their anger and hatred.

We don’t think it’s like that. The people who are hurting us are using sticks or throwing stones at us, but we get angry at them. Why be angry with them, seeing they are driven to hurt us by something else, by their hatred. Therefore, we should be offended by their anger.

42. In the same way, in the past

It was I who injured living beings.

Therefore it’s right that injury

Comes to me, their torturer.

In the past, I hurt those who I consider are my enemies, so it’s actually my fault that they are hurting me now. Driven by karma, they have no other choice than to take revenge. Since we deserve it, who should we be angry at? At the end of this passage it says:

47. Those who harm me rise against me.

It’s my karma that has summoned them.

And if through this these beings go to hell,

Is it not I who bring their ruin?

Due to having hurt them in this or a past life, it’s our karma that causes others to hurt us. But, as a result, they are accumulating bad karma and therefore will fall to hell. Aren’t we the ones who bring their ruin? Aren’t we the ones who have brought them harm?

48. Because of them and through my patience.

All my sins are cleansed and purified.

But they will be the ones who, thanks to me,

Will have the long-drawn agonies of hell.

If we can practice patience, we can cleanse ourselves of misdeeds that we committed. We can act virtuously and accumulate great merit. Those who hurt us will be the ones who have to suffer the agonies of hell. The next stanza tells us:

49. Therefore, I am their tormentor,

And it’s they who bring me benefit.

Thus, with what perversity, pernicious mind,

Will you be angry with your enemies?

50. If a patient quality of mind is mine,

I shall avoid the pains of hell.

But though indeed I save myself,

What of my foes? What fate is in store for them?

We should think, “It’s because of me and therefore it’s my problem that they will fall into hell - I am their tormentor. They bring me benefits, so I’m being helped by practicing patience in such situations. I should be happy that they are giving me the opportunity to practice. I should be grateful and say to them, ‘Thank you very much. It’s wonderful.’”

This has been the teaching on being patient with the things that are displeasing to us. Then there is the discussion about the need to be patient with scorn, harsh words, and criticism.

Sometimes people are scornful towards us, say harsh words, or criticize us, but there’s no point in getting angry when this happens. This is taught in stanza 52:

52. Because if mind is attached to the body,

This body is oppressed by pain.

Because the mind is not a physical body,

It cannot be destroyed by anyone.

There are two ways someone can harm us, physically or mentally. But the mind isn’t a solid body. So, how can it be harmed and who can harm it? Our body can be harmed, but

53. Scorn and hostile words,

And comments that I don’t like to hear –

My body isn’t harmed by them.

What reasons do you have, O mind, for your resentment?

Who do such things actually harm? Nobody. So why be annoyed and angry when this happens? Hostile words don’t harm our mind, so why not just put up with them? Sometimes we think that rumors will cause others to not like us and therefore it’s fitting to be angry with people who speak badly of us. We should be patient with harsh words that other people say about or to us. Sometimes we think, “Their criticism will harm my income and livelihood:” We need to contemplate the next stanza, which says:

55. Perhaps I turn from it because

It hinders me from having what I want.

But all my property I’ll leave behind,

While sins keep me steady company.

It’s not right to get angry because we think someone’s bad speech will harm our livelihood. At some point we will have to give up all the money we earned, at the latest when we die. But our misdeeds will stay with us until the time they ripen.

56. Better for me to die today

Than live a long and evil life.

However long the days of those like me,

The pain of dying will be all the same.

So, being wealthy and having lots of possessions and a long life aren’t of that much benefit, because we will suffer losing them when we die.

57. One man dreams he lives a hundred years

Of happiness, but then he wakes up.

Another dreams an instant’s joy,

But then he wakes up, too.

58. When they wake up, both of their happiness

Is finished, never to return.

Likewise, when the hour of death comes around,

Our lives are over, whether brief or long.

If someone dreams living a hundred years having a wonderful time and another person dreams of being happy for an instant, their dreams are different, but waking up is the same for both of them. The same with dying and death; it’s the same for those who live long and for those who have a short life.

59. Though we be rich in worldly goods,

Delighting in our wealth for many years,

Despoiled and stripped as though by thieves,

We must go naked and with empty hands.

If we are rich and own many things, in the end it will be as if bandits have stolen everything from us and we have to go impoverished. For this reason, we shouldn’t see harm and difficulties as problems; they don’t really harm us.

So, for the three objects we get angry at - when we feel that we have been hurt, when we feel that friends or relatives have been hurt, when we feel our enemies have been pleased -, we have gone through the first.

We are discussing the sixth chapter on patience of The Way of the Bodhisattva. It deals with always remembering the faults of anger and of having mindfulness and awareness so that we can develop patience.

When we contemplate patience, we need to know the benefits of having patience and think about them again and again so that we put it into practice as much as possible. By being interested in the benefits of having patience, we will be able to practice and develop it more and more. As a result, we will be able to diminish our anger and finally give it up.

As mentioned, there are three types of patience: there is patience with harm done to oneself, patience with harm done to our relatives and friends, and patience when our enemies are helped. I have discussed the first and we saw that we might lose patience and become angry with someone who hurts family members or friends. We should not let that happen.

As to the Dharma, which is our main support and friend, the 64th stanza says:

64. Even those who vilify and undermine

The Sacred Doctrine, images, and Stupas

Are not proper objects of our anger.

Buddhas are themselves untouched thereby.

We might think, “I can put up with being hurt, but it’s alright to get angry if somebody destroys a statue of Buddha, hurts a Buddha in some way, tears down a Stupa that contains sacred relics, destroys volumes of Dharma texts, or rebukes the Dharma.” If somebody does something like that, it isn’t right to get disturbed or angry about it. We must also be patient then. What is the purpose of being patient in such cases? In fact, the Buddha can’t be torn down. Furthermore, the blessings aren’t lost if someone demolishes a Stupa, nor is the truth harmed if someone refutes the Dharma. So, there’s no reason being angry when someone does things like that. Similarly, nothing can harm the Three Jewels. But sometimes we think it’s different when it comes to our Lamas, spiritual friends, family members, or friends and think it’s alright to get angry and retaliate if they are harmed.

65. And even if our teachers, relatives, and friends

Are now subject to aggression,

All derive from factors, as explained.

Thus we should perceive and curb our anger and wrath.

Due to being overcome by afflictions and lacking control, it’s not somebody’s fault if he or she hurts our Lamas, spiritual friends, relatives, or friends. We need to practice patience.

Generally, as said about harm done to us, there are three types of patience: the patience of suffering, the patience of recognizing the Dharma, and the patience of not thinking anything about problems that arise. Because we do not experience suffering then, the first type does not refer to patience of taking suffering upon ourselves. So, there are two sections to this: the patience of recognizing the Dharma and the patience of thinking others are not at fault when we are harmed, because they don’t know what they are doing.

66. Beings suffer injury

From lifeless things as well as living beings.

So why be angry only with the later?

Rather, let us simply bear with harm.

Sometimes we are threatened and harmed by living beings who have a mind, sometimes by things that don’t have a mind. When threatened by somebody who has a mind, we think, “That’s an enemy. It’s alright to be angry. I have to fight back.” When we are harmed by something that doesn’t have a mind, we think, “Things happen” and see that it’s useless getting angry. But the reasoning in both cases is the same. If it’s not alright to get angry at things that don’t have a mind and harm us, why get angry at somebody who has a mind and harms us? We understand that they have no control and practice patience.

In terms of the person who is harming and the person being harmed, we sometimes think that the person being harmed should be angry. As said in the 67th stanza:

Some do evil things because of ignorance,

Some respond with anger because of ignorance.

Which of them is faultless?

To whom shall error be ascribed?

Due to the power of ignorance, some people get into fights and hurt somebody else, who in turn becomes angry and retaliates. Which of the two are at fault? Both are under the power of ignorance, so it’s pointless and unreasonable to get angry.

Instead, why did they act in times gone by

That they are now so harmed by others’ hands?

Since everything depends on karma,

Why should I be angry at such things?

The above stanza is easy to understand, so let us continue with the next one. It says:

This I see and therefore, come what may,

I’ll hold fast to the virtuous path

That fosters in the hearts of all

An attitude of mutual love.

What should we do when we see that somebody is harming our Lamas, relatives, or friends? We should understand that they are acting under the power of bad circumstances and that we need to have an attitude of Bodhicitta, i.e., loving kindness and compassion for the person being hurt and the person who is hurting. That’s what we need. We need to make sure that we don’t wish to harm anybody and act accordingly. We practice patience in this way and are thus on the virtuous path of accumulating virtue and merit. It’s important for us to always stay on the right path and lead our lives in the direction of love and compassion. An example is given in the next stanza:

Now, when a building is ablaze

And flames leap out from house to house,

The wise course is to take and fling away

The straw and anything that causes the fire to spread.

If we see that our neighbor’s house is burning, we make preparations and remove anything from our house that might catch fire, being sure that it won’t burn. In the same way:

And so, fearing that merit might be consumed,

We should at once cast far away

Our mind’s attachments, which are

Tinder for the fiery flames of hate.

Sometimes we have things on our mind that we are attached to and like. To avoid getting angry and being consumed by the fire of anger by thinking something will happen to those things, we need to get rid of them.

When someone has hurt and caused us or our friends suffering and pain, we need to be patient. We need to bear with that suffering, as the next stanza says:

Is it not a happy chance if, when condemned to death,

A man is freed, his hand cut off in ransom for his life?

And is it not a happy chance if now, to escape hell,

I suffer only the misfortunes of the human state?

If, for example, an evil-doer has been condemned to death, it takes many legal procedures for the verdict to be lifted and the hand of the criminal to be cut off as punishment for his actions before he is set free. Such a person is happy to have been saved and to be free again, so he doesn’t think it was really that bad just losing his hand. In the same way, it’s very beneficial to bear any suffering that we might have and not to think that we won’t receive any help.

Furthermore, it is the case that if we are angry and fight with people, then we will go to hell and experience greater suffering. So, if we experience harm, don’t get angry, but bear the pain, then we and the person who hurt us will benefit by not having to go to hell, which is very good. That’s why we must bear suffering and pain with patience.

If even these, my present pains,

Are now beyond my strength to bear,

Why do I not cast off my anger, which

Is the cause of future sorrow in infernal torment?

If we fail to bear problems that are the cause of anger, we won’t be able to overcome suffering. We need to rid ourselves of all suffering as well as the cause and the outcome, which is experiencing the hell realms. To do that, we need to give up the cause for going to hell, which is anger. Therefore we need to make sure that we don’t get angry.

If we recollect all the afflictions we have had, we find that we have committed many wrongs due to having followed after them. As a result, we have fallen into the hell realm, or into the hungry ghost realm, or into the animal realm. We have experienced all sorts of suffering while in the human realm, too. So, since beginningless samsara, has it helped us to follow after the affliction of anger? Has it helped others? No. The text tells us that

For the sake of gaining all that I desired,

A thousand times I underwent

The tortures of the realms of hell,

Achieving nothing for myself and others.

The present aches are nothing in comparison with those,

And yet, great benefits will come from them.

These troubles that dispel the pain of wanderers,

It’s only right that I rejoice in them.

We might presently have a small problem or an ache, but it brings a great benefit if we are patient; we can gather great merit, will not increase our afflictions, but will be able to eliminate them. Therefore it’s said, “These troubles that dispel the pain of wanderers, it’s only right that I rejoice in them.” This means that if we are patient with problems and suffering, we won’t bring suffering to ourselves or to others. We can think, “That turned out well. It was very helpful for me and for others. It’s only right to rejoice.” So, we should be really happy that we were able to practice patience while suffering.

Of the three objects of not getting angry but practicing patience, we went through not getting angry at harm done to us. Then we went through not getting angry at harm done to our Lamas, the Buddha, to sacred objects, or to our friends and relatives. Now we will look at not getting angry when good things happen to our enemies.

Sometimes we are angry when good things happen to our enemies, e.g., when somebody who hurt us becomes famous or is praised. But we shouldn’t, because it harms us. We should practice patience instead.

When others take delight

In giving praise to those endowed with talents,

Why, O mind, don’t you likewise

Find joy in praising them?

When something good is written or said about someone we don’t like, we should be happy and think, “That person really has good qualities.” We should ask ourselves, “Why don’t I have the same joy as others have about their good qualities?” If we can praise our enemy’s qualities, we would also be able to rejoice in them as well.

The pleasure that is gained from that

Gives rise to blameless happiness.

It’s urged on us by all the Holy Ones

And is the perfect way of winning others.

Having much attachment to happiness can lead us to act non-virtuously. There’s nothing harmful about praising and rejoicing in others’ positive qualities and prosperity. In fact, it’s good - it’s a wonderful way to be.

“But they are the ones who will have the happiness,” you say.

If this is the joy that you resent and

You thus don’t pay wages or return favors,

You will be the loser, both in this life and in the next.

We might think, “I don’t like it when my enemies are praised or become famous. This is not good for me.” If we think this way and don’t rejoice in their success, it won’t turn out well for us in this life.

When praise is heaped upon your qualities,

Your’re keen that others should be pleased about it.

But when the compliment is paid to others,

You feel no inclination to rejoice as well.

Who is happy when people say, “Oh, that person is really good”? Other people. If we just sit there and have no inclination to feel happy about others’ joy, it doesn’t help anyone at all. But not feeling joy about others’ success is going backwards. The next stanza tells us why it’s not alright to be angry when our enemies are happy.

Sometimes someone has harmed us and when we see that someone else is helping them and they are happy, we think, “The person who has hurt me is being helped. That’s not right.” Instead of being patient, we become annoyed and angry. The stanza says:

You who want the happiness of beings

Have made the wish to be enlightened for their sake.

So why should others irk you

When they find some pleasure for themselves?

We have Bodhicitta and recite the wish of The Bodhicitta Prayer, which is: “I want all sentient beings to be happy and to have the causes of happiness.” We meditate on immeasurable love and compassion. We have this wish and make the commitment that we want to work for the benefit of others, so is it appropriate to be angry when someone we don’t like is happy or becomes famous? No. There’s a reason why that person has gained happiness, and we can rejoice in that.

And if you claim to wish that beings

Be enlightened, honored by the triple world,

When petty marks of favour come their way,

Why are you so discomforted?

We recite, “I want to gain Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings. May everyone become a Buddha,” but if someone who hurt us is popular, we aren’t patient. Why, then, did we make the commitment?

When dependents who rely on you,

To whom you are obliged to give support,

Find for themselves the means of livelihood,

Will you not be happy? Will you once again be angry?

If even this you do not want for beings,

How could you want Buddhahood for them?

And how can anyone have Bodhicitta

Who is angry when another prospers?

For example, if someone is dependent upon us and we give them food, clothing, and so on, will we be angry when someone else gives them things? There’s no reason. Also, it’s a kind of lie to recite the prayer to attain Buddhahood and to have the wish that all beings be happy if we don’t bear slight harm and are unhappy when others experience good.

We have gone through being patient when we are harmed, when our friends are hurt, and when our enemies are benefitted. We need to cultivate and perfect patience in those three situations. We need to know this and not be angry when these things happen. We need to think about this again and again and realize that we don’t benefit at all if we become angry in those situations and aren’t patient.

Sometimes we have obstacles that prevent us from getting what we want. We need to make sure that we don’t lose ourselves to anger in those situations and that our patience doesn’t weaken then. It can happen that we feel good when we learn that something bad happened to someone we consider our enemy. This is not right, as stated in the 87th stanza:

87. If unhappiness befalls your enemies,

Why should this cause you to rejoice?

The wishes of your mind alone

Will not contrive their injury.

When our enemy is unhappy, there’s no reason to think, “This is great!” Thinking like this doesn’t help our mind in any way; it doesn’t change their situation nor benefit us either.

88. If your hostile wishes were to bring them harm,

Again, what cause of joy is that to you?

‘Why then would I be satisfied?” – are those your thoughts?

Is anything more ruinous than that?

One of the worst thoughts we can have is thinking, “I’ll be really satisfied and happy if my enemy is hurt.” It’s a very black and terrible thought, as said in the next stanza:

89. Caught on the hook, unbearable and sharp,

Cast by the fisherman, my own defilements,

I’ll be flung into the cauldrons of the pit

And surely be boiled by all the janitors of hell.

In this analogy, our afflictions of hatred and anger are the fisherman who casts the hook that we bite into, that flings us about, and that will cause us to experience immense suffering. If we are caught by that hook, we will be flung into hell. Therefore we must make sure that we aren’t caught by this black mind of ours.

As said, we might be angry and lose our patience when learning that good things happen to our enemies. The verse above is a teaching about the reason and obstacle to practice patience when good things happen to those individuals or beings that we think are our enemies. Being patient with the suffering that we and our friends experience is taught separately, whereas the teaching about obstacles to our own happiness and that of our friends is taught together. We like when we or our friends are praised, and we become angry if something gets in the way. But that’s not right, as said in stanza 90:

90. Veneration, praise, and fame

Serve not to increase merit or my span of life.

They don’t bestow health or strength

And nothing for the body’s ease.

So, being praised and becoming famous don’t help us in any way; they are just as empty as the blowing wind. For this reason, the next stanza tells us that

91. If I am wise in what’s good for me,

I’ll ask what benefit this brings.

If it’s entertainment I desire,

I might as well resort to alcohol and cards.

We should think about what really benefits us. Does praise bring us any benefit? No. If we want to be happy and content and think, “If it’s entertainment I desire, I might as well resort to alcohol and cards.” Seeking praise is like going out and having a beer or something like that and doesn’t do any good. Also, not only does praise not help us, it harms us.

92. I lose my life, my wealth I squander,

All for the sake of my reputation.

What use are words and who will they delight

When I am dead and in my grave?

We spend all our energy and money to become famous, but isn’t that a waste? We risk our life to become a hero, but get killed. Who does that help? Nobody. We won’t be happy about having become a hero after we have been killed. In both of these cases, we resemble children who don’t stop crying when the sandcastles they built crumble and fall apart.

93. Children can’t help crying when

Their sandcastles come crumbling down.

My mind is so like them

When praise and reputation begin to fail.

When they are at the beach, children often work very hard at building a sandcastle. The child cries “Mummy, mummy” when it falls apart, but it’s pointless. There’s no danger of building a sandcastle and no danger when it falls down. Trying to build our reputation is just like that. When we lose our reputation, we are like children who have childish thoughts. So it’s better not to be praised and not to be famous. The 98th stanza tells us why.

98. Praise and compliments distract me,

Sapping my revulsion with samsara.

I become envious of others’ good qualities,

And thus all excellence is ruined.

When we are praised and famous and things seem to be going well for us, we are very distracted, are proud, and thus don’t feel weary of samsara. We are jealous of others and become competitive when we see or learn about their qualities. Then our Dharma practice is ruined, even destroyed. For this reason,

99. Those who stay close by me,

Damaging my good name and cutting me down to size,

Are surely there protecting me

From falling into realms of grief.

This means to say that those who are criticizing us and who are presenting an obstacle when we are casting ourselves into lower realms by chasing after wealth and fame are helping us – it’s actually very good, because

100. I am one who strives for freedom.

I must not be caught by wealth and honors.

How could I be angry with those

Who work to free me from my fetters?

Fame and fortune are fetters that bind us, so those who criticize us are actually helping us accomplish our wish, which is to become free from samsara. Why become angry with them?

101. They, just like Buddha’s blessing,

Bar my way - determined as I am

To dive head-long into sorrow.

How can I be angry with them?

As it is, we are meeting preparations to run straight into the lower realms of existence, and those who criticize us are actually like the blessing of the Buddha. They are preventing us from experiencing immense suffering. So they are being really kind to us. It’s not right being angry with them by losing our patience.

In the same way, we also have to be patient with individuals who prevent us from being helpful and from doing good. It’s said in the next stanza:

102. I shouldn’t be irritated, saying,

“They are obstacles to my good deeds.”

For is not patience the supreme austerity,

And should I not abide by this?

We accumulate merit by being patient with those who present obstacles for practicing the path. If someone hurts us, we should think, “What a poor person. I have to have compassion.” In this way, by being patient, that person is actually causing us to accumulate merit. If we are impatient in those situations, then we are the ones who are preventing ourselves from accumulating merit. As said in the stanza:

105. The beggars who arrive at proper times

Aren’t an obstacle to generosity.

We cannot say that those who give the vows

Are hindrances to ordination.

There must be a recipient of our gifts if we want to be generous, therefore beggars “… aren’t an obstacle.” A beggar is really good and has arrived just when we wanted to give money, food, or other things. In the same way, those who can impart the vows of a nun or monk are not a hindrance to ordination. Likewise, someone who causes problems is not a hindrance for practicing patience. On the contrary, this person presents a wonderful chance to practice patience and is therefore a fortune. In any case, there are many people to give to if we want to be generous.

106. The beggars in this world are numerous;

Assailants are comparatively few.

For if I do no harm to others,

Others do not injure me.

If nobody hurts us, it’s difficult finding someone with whom to practice patience.

107. So, like a treasure found at home,

Which I have gained without fatigue,

My enemies are helpers in my Bodhisattva work,

And therefore they should be a joy to me.

It’s like sitting at home and not doing anything. Suddenly and unexpectedly we find a huge treasure, which is wonderful. Likewise, the best way to accumulate merit is by practicing patience, but we need someone to be patient with. It’s a great treasure when there’s somebody who causes us to be patient. Thus,

108. Since I have grown in patience

Thanks to them,

To them its first fruits I should give,

Because they have been the cause of my patience.

When the assailant and the person being patient come together, we can actually practice patience and accumulate merit. Therefore we should share the results of our merit with our so-called enemies, because they are the ones who have caused us to accumulate merit by being patient. We can doubt this and think, “Okay, the enemy and I have come together and I was patient, but there’s no reason to share the merit of the virtue that came out of this.” The next stanza says:

109. And if I think that my foes don’t deserve to be honored,

Because they didn’t intend to arouse my patience,

Why do I revere the Sacred Dharma,

The cause of my attainment?

If we think there’s no reason to share the merit of our practice with those who wanted to harm us and didn’t in the least intend to help us, then why revere the Sacred Dharma that doesn’t have thoughts of helping us? The answer is given in the next stanza, which says:

110. “These enemies conspired to harm me,” I protest,

“And therefore they shouldn’t be honored.”

But had they worked like a doctor to help me,

How could I give rise to patience?

We think that those who intended to harm us or who are harming us aren’t worthy of veneration, but they helped us practice patience more than a doctor could. Without them, we wouldn’t be able to practice patience. The text states:

111. Thanks to those whose minds are full of enmity

I engender patience in myself.

They therefore are the causes of my patience,

Fit for veneration, like the Dharma.

Are those who wish to hurt us or who are hurting us worthy of veneration? Yes, because they present the opportunity to practice patience. For this reason, they are like the Buddha.

112. And so the mighty Sage has spoken of the field of beings

As well as of the field of Conquerors.

Many who brought happiness to beings

Have passed beyond, attaining perfection.

There are the fields of the Conquerors or Buddhas and the field of sentient beings. They aren’t different in terms of those dwelling there who help sentient beings. Just as the many Buddhas and Bodhisattvas who helped in the past have attained perfection and passed beyond, it’s because of sentient beings that we are able to attain the ultimate result.

113. Thus the state of Buddhahood depends

On beings and on Buddhas equally.

What kind of practice is it

That honors only Buddhas, but not beings?

So, it isn’t right to respect and honor the Buddhas, but to get angry and not to be patient with sentient beings.

114. Not in the qualities of their minds,

But in the fruits they give are they alike.

In beings, too, such excellence resides,

And therefore beings and Buddhas are the same.

115. Offerings made to those with loving minds

Reveal the eminence of living beings.

Merit that accrues from faith in Buddha

Shows in turn the Buddha’s eminence.

It’s most important to cultivate Bodhicitta. Sentient beings make it possible for us to practice patience and loving kindness and to meditate on compassion - it would be impossible without them. We have faith in the Buddha. In this way, sentient beings and the Buddha are alike.

116. Although not one of them is equal

To the Buddhas, who are oceans of perfection,

Because they have a share in bringing forth enlightenment,

Beings may be likened to the Buddhas.

If we can practice patience and treat sentient beings well, then we are fulfilling the wishes of the Buddha and the Buddhas. As it says in the next verse:

119. The Buddhas are my true, unfailing friends.

Boundless are the benefits they bring to me.

How else may I repay their goodness

Than by making living beings happy?

The Buddhas, who benefit everyone, are the great friends and companions of all sentient beings. We want to please them and wish to repay their kindness. The best way to do this is to be respectful of all sentient beings and to help them become happy. This will please the Buddha and the Buddhas - there’s no other way.

122. Buddhas are made happy by the joy of beings.

They are sorrowful and lament when beings suffer.

By bringing joy to beings, then, I also please the Buddhas;

By wounding them, I also wound the Buddhas.

This stanza tells us that we please the Buddhas when we make others happy, whereas we displease the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas when we hurt others and aren’t patient with them. Helping sentient beings and making them happy is the same as venerating and making offerings to the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. Hurting others is the same as hurting the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. So we must be very careful and never get angry or hurt anyone.

Again, we need sentient beings in order to make offerings to the Buddhas. As taught in the next stanza, there’s no other way to do this.

123. Just as there’s no sensual delight

To please the mind of one whose body burns in fire,

There’s no way to please the Great Compassionate Ones

While we ourselves cause another’s pain.

Will eating candy make somebody who is being burned alive happy? No. Likewise, “There’s no way to please the Great Compassionate Ones while we ourselves cause another’s pain.” There’s no way we can please the Buddhas as long as we hurt others.

124. The damage I have done to beings

Saddens all the Buddhas in their great compassion.

Therefore, all these evils I confess today

And pray that they will bear with my offences.

We have harmed many sentient beings. Since it saddens all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas and we want to please them, we confess our misdeeds in their presence and pray that they excuse us. Then:

125. That I might rejoice the Buddhas’ hearts,

Henceforth I will be master of myself, the servant of the world.

Though crowds may trample on my head and try to kill me, I shall not seek revenge.

Let the Guardians of the world rejoice!

We will be able to please the Buddhas if we don’t get angry at crowds who trample on us, kick us, or walk on our heads.

Stanza 127 speaks about the benefits and qualities that arise from practicing patience. It says:

127. This very thing is pleasing to the Buddhas’s hearts

And perfectly secures my welfare.

It will drive away the sorrows of the world,

And therefore it will be my constant work.

If we please the Buddhas by practicing patience well, we will be securing our own well-being. We have to have patience in order to dispel all sorrows in the world and to bring happiness to everyone. Several stanzas in the text give examples for this; I will only speak about the 133th, which says:

133. No need to mention future Buddhahood,

Which is achieved by bringing happiness to beings.

How can I not see that glory, fame, and pleasure,

Even in this life will likewise come?

There’s no need to mention that in the future we will become Buddhas if we practice patience and if we respect all sentient beings. In the short term, we will have accumulated much merit and thus everything will go well for us in this life. The ultimate and temporary results of practicing patience are addressed in the above stanza, the temporary results in more detail in the next stanza:

134. For patience in samsara brings such things

As beauty, health, and good renown.

Its fruit is great longevity,

The vast contentment of a universal monarch.

This completes the discussion of the 6th chapter on patience as it has been handed down to us by Shantideva in The Bodhicharyavatara.

There aren’t any particular meditation practices to cultivate patience, rather, we think about why it’s beneficial and put it into practice. When we experience difficulties, are suffering, or run into an enemy and afflictions of anger and hatred arise in us, we should think, “This is what is taught in Shantideva’s The Way of the Bodhisattva.” If we do this, we will be able to apply the antidote and change our way of thinking. We will experience inconceivable benefits if we remember these teachings again and again and put them into practice. -- Thank you!

Dedication

Through this goodness may omniscience be attained

And thereby may every enemy (mental defilement) be overcome.

May beings be liberated from the ocean of samsara

That is troubled by waves of birth, old age, sickness, and death.

By this virtue may I quickly attain the state of Guru Buddha and then

Lead every being without exception to that very state!

May precious and supreme Bodhicitta that has not been generated now be so,

And may precious Bodhicitta that has already been never decline, but continuously increase!

A Long Life Prayer for Thrangu Rinpoche,

composed by His Holiness the XVIIth Gyalwa Karmapa

Within the edgeless, centerless Mandala of Dharma expanse

Your life is space’s Vajra essence, permeating space.

We ask that you please stay, indestructible within

The locket of the sun and moon, unchanging, never leaving.

These teachings were published in Thar Lam - The International Journal of Palpung, New Zealand, April 2011, pages 30-53. The beautiful lotus was graciously offered by Yeunten, Nguyenthi Mydung from Paris. Thank you Yeunten for your sincere dedication. -- This article was rewritten, edited slightly & arranged by Gaby Hollmann (contributor to Thar Lam) for visitors of this website & for personal use only. All rights reserved. -- May the Dharma flourish & everyone without exceptions experience peace & well-being! – Easter, April 2011.