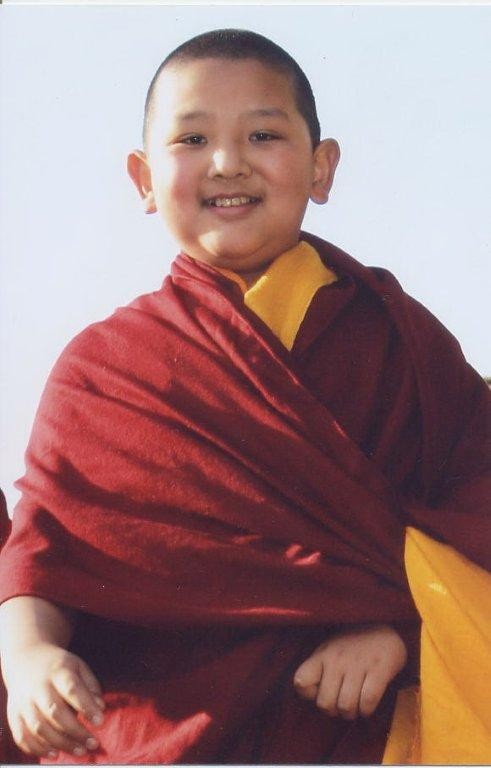

Jamgon Kongtrul Yangsi

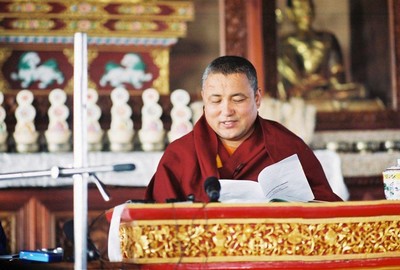

Venerable Drupön Khenpo Lodrö Namgyal

Instructions on

"An Elucidation of the Treatise,

'The Essence of the Three Principal Aspects of the Path'

by Je Tsongkapa"

composed by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye the Great

Because of the many pages her a pdf-version to download

Presented at Karma Chang Chub Choephel Ling, Heidelberg, in December 2009.

This article of teachings that Drupön Khenpo Lodrö Namgyal generously imparted

is dedicated in memory of His Eminence the Third Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche,

Karma Lodrö Chökyi Senge (1954-1992),

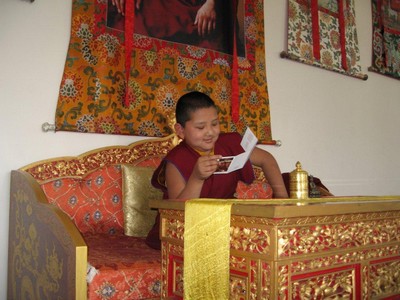

to the long life of His Eminence the IVth Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche, Lodrö Chökyi Nyima,

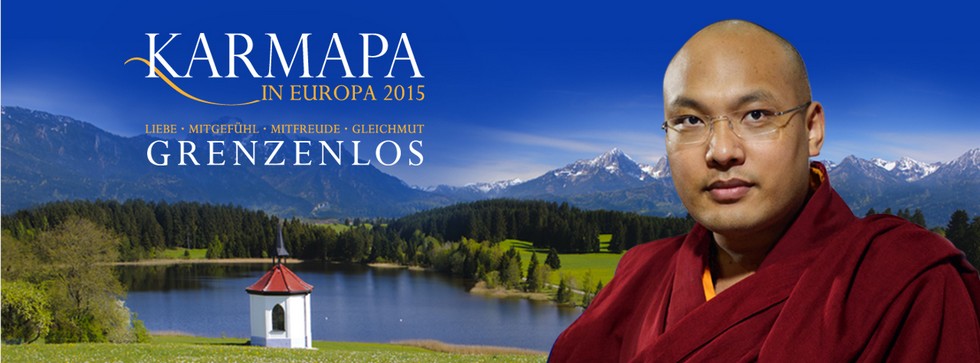

of His Holiness the XVIIth Gyalwa Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje, and

of all prestigious Khenpos and Lamas of the Karma Kagyü Lineage, and

to the preservation of the pure Lineage of Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye.

Venerable Drupön Khenpo Lodrö Namgyal completed his studies with highest distinctions at Nalanda Shri Institute for Higher Buddhist Studies at Rumtek Monastery, the Seat of His Holiness the Gyalwa Karmapa in Sikkim. Being the personal tutor of His Eminence the IVth Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche, Drupön Khenpo Lodrö Namgyal is the director of Lava Kagyü Thekchen Ling Monastery Lava. He is also the main teacher for the Rigpe Dorje Study Program at Pullahari Monastery, the Seat of His Eminence Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche. The sacred Monastery of Pullahari is located in the foothills north of the Great Stupa of Boudhanath in Kathmandu, Nepal. In the secluded serenity with spacious views, the age-old tradition of prayers, rituals, training, and education of monks continues in the monastery and also in the Mahamudra Retreat Centre. In addition, residential programs for lay practitioners are offered at the Rigpe Dorje Institute every year, and the facilities for individual retreat are open throughout the year.

Introduction

Let me greet and welcome you kindly to this seminar. Before beginning, please give rise to Bodhicitta, 'the mind of awakening,' i.e., the noble heartfelt wish to be able to liberate all living beings from the suffering of samsara and lead them to perfect awakening of Buddhahood by receiving and awakening to the Dharma teachings. Which teaching will we be looking at? The three outstanding aspects of the path of Dharma according to the text, sNying-po-lam-gtso-rnam-gsum-'di-rmäd-byung " The Essence of the Three Principal Aspects of the Path. Who is the author of this root text? Je Tsongkapa. Why is this text special for us? Because Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye composed a commentary to the root text by Je Tsongkapa.

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye was the incomparable 19th century scholar and master who initiated Ris-med. Rime became the non-sectarian movement that embraced the various Buddhist traditions in Tibet. He collected and compiled all authentic Dharma texts that were studied and practiced in Tibet and authored commentaries to texts that seemed incoherent or difficult to comprehend into his great collection of invaluable scriptures. His most precious collection of scriptures is known as mDzöd-chen-lnga " The Five Great Treasures. The commentary that he composed to the root text that we will be looking at together is entitled An Elucidation of the Treatise, 'The Essence of the Three Principal Aspects of the Path' by Je Tsongkapa. It is included in the gDam-ngag-mdzöd " The Treasury of Precious Key Instructions, which is one of the five main sets of scriptures in The Five Great Treasures.

Eight great transmission lineages of Buddhism were brought to Tibet from India. They are referred to as "The Eight Chariots of the Practice Lineages." Since Tsongkapa (who lived from 1357-1419 C.E.) belonged to the Kadam Tradition, which is one of the Eight Great Chariots of Transmission, Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye's commentary to the root text by Tsongkapa is in the section of the Kadampa in The Treasury of Precious Key Instructions, the gDam-ngag-mdzöd.

Who are the Kadampa? The Kadam Tradition dates back to Jowo Pälden Atisha, who was one of the most revered Indian saintly scholars of the 11th century. He was invited to bring the words of the Buddha to Greater Tibet after Buddhism had been disrupted there. He established a correct understanding of the Buddhist teachings in Tibet and assisted translators in their endeavour of rendering sacred Sanskrit texts into Tibetan faithfully. Jowo Atisha had many disciples and followers. His heart son, Dromtön Gyalwa Jungney, became the First Kadam Lineage-Holder and established the tradition in Tibet.

The Tibetan term for Kadam is bka'-dams and means the 'Sacred Words of the Buddha.' The cycle of teachings that Lord Buddha presented when he turned the Wheel of Dharma three times are gradated paths or vehicles of practice (yana in Sanskrit, theg-pa in Tibetan). The three yanas are instructions that followers practice in successive order to attain the same goal, which is great awakening. Followers of the Kadam Tradition take each word that the Buddha spoke to heart and regard every word as a guideline for their practice.

Why am I mentioning this? Because often people are biased when there is a discussion of the three vehicles (theg-pa-gsum). Even though they are referred to as "the smaller vehicle" (Hinayana, theg-pa-dmän-pa), "the great vehicle" (Mahayana, theg-pa-chen-po), and "the supreme vehicle" (Mantrayana, theg-pa-gsang-sngags), the one is not better and not higher than the other. Since the instructions presented in all vehicles are directed towards achieving the same goal and are very beneficial, every path is good. "Then," we might ask, "why did the Buddha teach the three paths if they are one and the same?" Without being discriminative or judgmental, by presenting the three vehicles, the Buddha showed disciples how to gradually tread the path of Dharma according to their inclinations and capabilities. We might wonder, "Isn't the one more profound than the other?" The teachings of each vehicle accord with its followers' capacities, so this question can't be answered easily; it depends upon individuals. Seeing a disciple of Hinayana has the skills to understand and practice those specific teachings, he doesn't think that Mahayana is more profound; Hinayana is deeper for him than the others. He can understand and experience the Hinayana teachings that he practices on the path to liberation and would feel lost if he were instructed in the other vehicles. For example, nobody would say that Tibetan momos are better for human beings than milk. Momos are delicious dumplings consisting of different kinds of meat and vegetables that are wrapped in simple dough and cooked by being steamed over soup. Milk is better for a newborn and small baby, while a grownup would prefer nourishing momos that a baby can't digest. Therefore, what is better for somebody depends upon the individual. In the same way, not one of the numerous teachings that Lord Buddha presented is better or more profound than the other. They are profound in dependence upon an individual's ability to understand and benefit by studying and following that specific path.

When he was asked a similar question, if he thought Christianity is better than Buddhism, His Holiness the Dalai Lama responded, "I can't say that Christianity is better or worse than Buddhism. All I can say is that the words of the Buddha are better for me. Christianity might be better for many people, while other people benefit by believing in Hinduism. Everybody has specific propensities and capabilities, therefore it's not fair to generalize and say that one religion is better than all others. It would be wrong to think that everybody should follow it."

The Buddha taught that every living being without exception has the potential and capacity to attain full awakening, i.e., Buddhahood. Some disciples understand and immediately realize this, while others need to learn and practice the Dharma step by step. The different teachings are therefore presented in gradual succession so that everyone can progress in their spiritual practice at a pace that is appropriate for them. The three principal aspects of the path are meant for individuals who need to be guided gradually.

Disciples who are able to traverse the path of Dharma step by step first need to awaken the wish to attain liberation (nges-par-'byung-ba, also translated as 'renunciation') and concentrate their attention on entering the path to liberation. Having developed the wish firmly, it is secondly necessary to cultivate Bodhicitta (byang-chub-kyi-sems in Tibetan, 'the mind of awakening'). After having established Bodhicitta, it is thirdly necessary to have the right view (yang-dag-pa'i-lta-ba). Having the right view means that by virtue of wisdom-awareness (shes-rab), disciples progressively win direct insight (mngön-sum) into the true nature of all things (dharmata in Sanskrit, chös-nyid in Tibetan) and thus realize pristine, timeless wisdom, ye-shes.

Because of the short time at our disposal during this seminar, we won't be able to go through every word of the commentary that Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye composed to the root text, which is entitled The Essence of the Three Principal Aspects of the Path and was written by Je Tsongkapa. So, I will give a summary of the meaning of the commentary by refering to the verses of the root text.

a) The Offering

In the Buddhist tradition, it is the custom when writing a treatise to begin with the title of the treatise, then to pay homage by composing an opening line or verse of offering, and to present a short description of the purpose for writing the text. The homage that Tsongkapa wrote in the root textis:

/ rje-btsün-bla-ma-rnams-la-phyag-'tshäl-lo //

'I pay homage to all revered and exalted Lamas.'

Why do great masters and scholars begin Buddhist texts and treatises they compose with a homage of veneration to the exemplary Lamas and teachers? This is done so that the author doesn't encounter any hindrances while writing the text and so that in the future their work benefits others without any obstacles. How does this function?

Enthusiasm and fortitude arise in our mind when we pay homage to the exalted Lamas or masters we hold in highest esteem and revere in our heart. Through the virtue of receiving the blessings by paying homage, our obscurations are removed and our joyful enthusiasm to achieve the result of Dharma practice without hindrances increases. This is very practical, because we need to remove hindrances and establish conducive conditions for anything we hope to accomplish. Venerating our Lamas and teachers by paying homage to them with devotion cleanses us of our obstacles and bad habits and enables us to develop new good qualities. By paying homage, we receive the blessings of our Lamas. This gives us the strength and joy we need in order to practice and accomplish the Dharma.

Formulating or pronouncing devotion by writing or reciting an offering line or verse when beginning to write a sacred text or when giving Dharma instructions serves two purposes. It ensures that the author of a text or a scholar imparting teachings will complete the work well and thus it directly benefits him or her. Secondly, paying homage benefits students in that it gives them the opportunity to supplicate the Lamas with devotion before concentrating their attention on the instructions that follow. By doing this, obstacles are cleansed and bad habits, which are impediments for correctly understanding the teachings, are removed. Thus, due to the blessings we receive by paying homage, we are able to practice the path of Dharma with joy and fortitude.

Seeing that it's possible to experience joy and fortitude through the elimination of hindrances and obstacles with other means, why is paying reverence said to be so decisive? Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye tells us in the commentary he composed that the best way to remove hindrances and obstacles is to cultivate reverent devotion. It removes the main hindrance to our study and practice, the main hindrance being conceit, arrogance, pride. As long as we don't rely on exemplary masters and teachers, we won't be able to progress in our spiritual pursuit. This is the reason Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye stated that reverent devotion is the extraordinary method to have the enthusiasm and fortitude we need for our practice. It is the outstanding method to be cleansed of our bad habits and obstacles and prevents them from arising again.

The presence and absence of pride distinguishes ordinary people from reliable and authentic persons. The characteristic of ordinary people is pride, nga-rgyäl. The characteristic of authentic, reliable, and honourable individuals is being free of arrogance and pride, nga-rgyäl-bräl-ba. Pride is the negative mental force that stops us from allowing new and better qualities of being to mature in us. It can be compared to a balloon that is thrown into water. An inflated balloon will always stay afloat and won't sink if it is thrown into a tub filled with water. In the same way, pride will always prevent us from becoming absorbed with beneficial qualities of worth. A better example for the inability to absorb and assimilate new good qualities due to being conceited and proud is being like a mountain peak when it rains. Rainwater, which symbolizes new good qualities, just flows down and away from the peak. By abandoning pride, we are like a valley in which the rainwater gathers. The first prerequisite for being an honourable person who can develop and mature is avoiding and abandoning conceit and pride, nga-rgyäl-spang-ba.

But what happens if a valley that absorbs the rainwater of good qualities is extremely deep? Not only the rainwater, but also the dirty water that inhabitants living in the surrounding villages and towns pour down the drain or into the nearby river flow into it. This illustrates what it means to demean ourselves by being polluted with bad qualities and is an example for being too discouraged and depressed to lead a good life, which helps nobody. We need to differentiate between being humble and feeling frustrated and depressed; it would be a grave error to think they are identical. Some people, who think they aren't proud, say, "I can't possibly accomplish anything. Everything is just too much for me." Being free of pride doesn't mean being a weakling. Thinking like this isn't being free of pride, rather, it's an excuse for being lazy. Just as we shouldn't take being free of pride as cowardice, we shouldn't confuse pride with courage. We need courage and should think, "Yes, I have the potential and skill to awaken. Yes, I can. I have the same potential and am just as skilled as the great masters who had extraordinary qualities, such as Manjushri, Asanga, Chandrakirti, and so forth. I will make best use of my potential and capabilities." Thinking like this is what having courage means. So, let's not mistake these things, but distinguish between humility and cowardice and between being proud and being courageous.

We have great veneration for Bodhisattva Manjushri, who is the manifestation of wisdom, and bow to his qualities because we understand and see that we, too, have the fundamental capacity to develop the same qualities. We wouldn't bow to him if we were proud and felt discouraged. What use would it be to prostrate before Noble Manjushri if we thought that we were totally unskilled and could never attain the qualities that he has? We prostrate before him because we appreciate and acknowledge that we have the same potential and capacity as he has.

The Tibetan term phyag-'tshäl (translated as 'homage') means 'dedicated veneration.' It consists of two words. Phyag denotes 'to remove' and in the homage it connotes removal of pride. 'Tshäl denotes 'to seek, to wish, to ask for' and in the offering line it connotes wishing to be able to realize qualities of worth. Therefore, two beneficial factors are addressed when expressing veneration in the homage; they are elimination of pride and awakening courage to tread the path. Without pride, but aware that we need to become better than we are, we take Bodhisattva Manjushri as our object of dedicated veneration. We realize that presently we don't have the extraordinary qualities of body, speech, and mind that he has and see the difference. Since he can set an example for us and we know that we have the ability to progress and become like him, we choose him as our object of veneration and model and don't choose somebody who is equal to us or less capable than we are.

Being free of the pride of thinking that it wasn't necessary to learn anymore, Je Tsongkapa took all reliable and authentic Gurus and masters as examples and developed the qualities they had by listening, contemplating, and meditating the Dharma that they taught him and that they lived by. He accomplished the goal in this way. Just as he accomplished the goal, we can look at the text that he composed and tell ourselves, "If Tsongkapa did it, so can I." We take those who have more qualities as examples, rejoice in them, allow that they inspire and encourage us to become free of pride, to awaken the courage to tread the path of Dharma, and to accomplish the goal without hindrances. This is the first step we take, having sincere and dedicated devotion and veneration for those who can guide us and following them.

b) The Intention and Commitment for Composing the Text

The first verse of the root text is a short description of the reason for writing the text. Tsongkapa stated:

/ rgyäl-ba'i-gsung-rab-kun-gyi-snying-po'i-dön /

/ rgyäl-sräs-dam-pa-rnams-kyis-bsngags-pa'i-lam /

/ skäl-ldän-thar-'död-rnams-kyi-'jug-ngogs-de /

/ ji-ltar-nüs-bzhin-bdag-gyis-bshäd-par-bya //

'For those who have the wish and merit to attain liberation, I will explain to the best of my ability the meaning of the essence of the Victorious One's ever most excellent speech, the saintly Bodhisattvas' praiseworthy path, and the entrance.'

Tsongkapa formulated his intention to complete this work when he wrote, "I will explain to the best of my ability." In which way is his intention and pledge relevant for us? After we started something, due to hindrances or laziness, we might be satisfied or pleased with having accomplished half or a part of our initial intention. If we clearly know what we want to accomplish at the start and feel committed to finish what we need to do, then, regardless of hindrances that arise and pass, we will continue and accomplish our aim. For example, we have to focus our attention on a target if we want to hit it with the arrow of our bow. But the string of our bow may not be too loose when we shoot the arrow, otherwise it will simply fall to the ground. It's not only necessary to identify a target, but we also need to have strength to shoot our arrow with our bow that is strung just right. In the same way, it's necessary to finish the work that has to be done in order to accomplish a goal that we have in mind. Tsongkapa formulated his intention quite clearly in this verse. He shows us that he was very aware of the importance and relevance of the very great task of composing the text that we are looking at here and that he had the willpower to carry it out and complete.

Furthermore, Tsongkapa was very aware of the necessity to compose The Essence of the Three Principal Aspects of the Path. He knew that he had to inform all fortunate persons who had the wish and skill to attain liberation about the entrance, 'jug-ngogs, i.e., they needed to know about the port so that they could start the journey. And the port or entrance is having knowledge of the three main aspects of the path. The excellent and sublime words of the Victorious One are the source that inspire and enable disciples to enter the path by boarding the ship of courageous compassion.

The three principal aspects of the path were the way of the Buddha's spiritual heirs, e.g., Bodhisattva Manjushri, Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, and so forth, and of the great human masters, e.g., Acharya Nagarjuna, Acharya Asanga, and so forth. Why did the Victorious One's spiritual heirs revere the three main aspects of the path as highly as they did? Because they saw that the three main aspects of the path - the wish to attain liberation, Bodhicitta, and the right view - are the qualities of the uncorrupted path. They are the three characteristics of the genuine and reliable path in that they ensure that disciples won't err, that the path is complete (i.e., that nothing is missing), and that the sequence of learning and practice aren't mixed up. Again, the true and genuine path is the right path, is complete, and is in consecutive order. The wish to attain liberation, having Bodhicitta, and having the right view ensure that the path to liberation is reliable and true. Let me exemplify this.

Let us imagine that we want to eat an apple, but there would have to be an apple tree. So, we would first have to have a definite source to grow an apple tree. We would have to have a sapling that will grow into an apple tree. If we mix saplings up and don't plant an apple tree sapling, one day we won't be able to pick the apple that we wanted to eat. Yet, merely planting an apple tree sapling won't guarantee that we will get an apple. So, secondly, we have to make sure that the sapling is provided with the many conditions it needs to grow into a tree, e.g., good earth, warmth, water, and so forth. Everything has to be complete so that nothing goes wrong. Thirdly, the conditions must be present in the right order, because, for example, the sapling would dry in the heat of the sun if it isn't watered at the right time. If everything goes well, the sapling we planted, irrigated, and fertilized will grow into an apple tree and will bear fruits that we can pick, hold in our hands, and eat. The process of working to achieve perfect awakening is also like this. To attain perfect awakening, we first have to make sure that we aren't on the wrong path. Secondly, we have to see to it that we have all conditions together so that we can practice correctly. Thirdly, we have to practice in the right order. When all three components are complete, we will be able to harvest the crop of perfect and complete awakening. To ensure that our endeavours to achieve this aim aren't in vain, Tsongkapa wrote that we need to have the three main aspects of the path, which are the wish to attain liberation, Bodhicitta, and the right view. With joyful determination, he wanted to share his insight with us and therefore composed the text, entitled The Essence of the Three Principal Aspects of the Path.

We see in the above introductory verse that Tsongkapa was very aware of the fact that the three aspects of the path are indispensable necessities that everyone seeking liberation must have and therefore should know about. He was determined and happy to contribute to this cause by composing this text on the three supreme aspects of the path that leads to awakening for the sake of his disciples and future generations. With decisiveness and enthusiasm, he did so and completed the work. In the same way, if we realize the necessity and importance of the task, then there is nothing that can cause us to turn away from our very good intention.

Both points (being wholeheartedly dedicated to noble and most excellent scholars and masters who set an example for us and being decisive to achieve the qualities they have) determine whether the instructions in The Essence of the Three Principal Aspects of the Path bear fruits. An example for both points is having the wish to hit a target with our arrow. Firstly, hindrances have to be removed, so we have to take care that the conditions are good by having a good arrow. We won't be able to hit the target if our arrow is crooked, too light, or too heavy. The arrow will fall to the ground if it's crooked or too heavy, which is the simile for being overwhelmed by the impediments of past bad habits that are lodged in us and that hinder us from wishing and striving to attain new good qualities. The arrow will fly around haphazardly if it's made of paper, which is the simile for not having enough enthusiasm and willpower. The first line of homage, the offering, is the method to remove our pride so that we have the courage to develop new good qualities, comparable with a good arrow. But a good arrow won't hit the target unless we pull the string of our bow and shoot it, which can be compared with the determination described in the above verse.

Tsongkapa composed both points as teachings for us. We, too, can develop the qualities that those we venerate have by becoming free of pride through paying respect to them and, knowing that we can achieve the same qualities they have, by being courageous and decisively doing what we need to do to achieve this goal. Having realized the necessity and importance of wishing to achieve liberation, of having Bodhicitta, and of having the right view, we resolve to receive teachings on the three principal aspects of the path, to contemplate and to practice them. Having learned about the preparations we just looked at, we are encouraged and know that we will be able to perfect and complete our intention. If we follow Tsongkapa's advice, we will see that he practiced what he taught and therefore is reliable. The stages he went through to attain the qualities that he had are a guide for us to emulate him.

c) Urging Students to Listen

Before presenting an explanation of the Buddha's teachings on the three main aspects of the path in the main body of his work, Je Tsongkapa urged his students to listen closely. He wrote:

/ gang-dag-srid-pa'i-bde-la-ma-chag-shin /

/ däl-'byor-dön-yöd-bya-phyir-brtsön-pa-yis /

/ rgyäl-ba-dgyes-pa'i-lam-la-yid-rtön-pa'i /

/ skäl-ldän-de-dag-dang-ba'i-yid-kyis-nyön //

'Those (of you) who don't cling to worldly pleasures, (but who) strive to make best use of (your) precious human life (and) with enthusiasm rely on the path that delights the Victorious Ones, fortunate ones, listen with wholehearted joy.'

What does this verse tell us? It informs all persons who are fortunate enough to want to tread the path that they need two things when receiving teachings on the three main aspects of the path. The two things are: upright enthusiastic interest and confidence that the path leads to a good result. Persons who have enthusiastic interest and confidence are fortunate and will be able to learn the three main aspects of the path. Being interested and having genuine confidence, they need to begin treading the path by hearing the teachings and then contemplating and meditating them.

In the above verse, Tsongkapa tells us that we will be listening to the teachings correctly if we are wholeheartedly interested. This points to an incorrect way of receiving the teachings when listening, which are the three faults that can occur and that we should not have. The three faults are traditionally compared to three containers. The first fault is likened to a bowl turned upside-down. Nothing can flow into and be contained in a bowl that is turned upside-down, which is like the fault of not really being interested. We need to be interested in the teachings, be appreciative, and joyful when receiving them. So the second fault is compared to a bowl with holes in the bottom. Whatever is poured into such a bowl leaks out again, which is like the fault of forgetting the teachings. The error of forgetting the instructions means not really being interested and not having enough devotion and confidence. We might be interested and remember what we heard, but we might have an improper motivation and not act in accord with the teachings. So the third fault is compared to a container that is turned upright, has no holes in the bottom, but is filled with rubbish and poison. Pure water that is poured into such a bowl automatically becomes contaminated. We need to be free of an impure attitude and motivation, kun-longs. That is why Tsongkapa begins his exposition by encouraging us to be open for the path by listening to the teachings with wholehearted interest, devotion, and joy.

We saw that the three principal aspects of the path are the wish to attain liberation, Bodhicitta, and the right view. Therefore the main body of the text begins with an explanation of the first aspect of the path, which is arousing the wish to attain liberation.

1. Arousing the Wish to Attain Liberation - Nges-par-'byung-ba

a) The Purpose

It is necessary to know the reason it is good to have the wish to attain liberation so that we are interested in practicing the path. Je Tsongkapa wrote:

/ rnam-dag-nges-'byung-med-par-srid-mthso-yi /

/ bde-'bräs-dön-gnyer-zhi-ba'i-thabs-med-la /

/ srid-la-brkam-pa-yis-kyang-lüs-cän-rnams /

/ kun-näs-'ching-phyir-thog-mar-nges-'byung-btsäl //

'Other than (first) giving rise to the wish for liberation, there's no other method for beings who have a body and are fully imprisoned in their thirst for worldly existence to become free from the ocean (of conditioned existence) and to find peace that is the fruit of bliss.'

This instruction means to say that all beings that have a body and are submerged in their thirst for worldly pleasures first need to arouse the wish to become free. In this verse, Tsongkapa teaches us that it's very important and necessary to give rise to the wish to become free, otherwise the experience of worldly happiness will continue deluding us, 'krul-pa. Whoever mistakes worldly happiness with the joy that can be experienced when free won't have the wish to develop and attain true and lasting joy, rather, his craving for worldly pleasures will increase more and more. Living beings who don't give rise to renunciation remain entrenched in the process of what can be called "addiction." An example for worldly pleasures that are wrongly taken to be reliable happiness is bait on the hook of a fishing pole. A fish believes that the bait it perceives on the hook will bring satisfaction, while in fact it is its doom. This example teaches us that we need to recognize that worldly pleasures are delusive and cause suffering. We will only have the wish to attain liberation and will seek genuine joy if we know that the true nature of delusory appearances is sdug-bsngäl, 'dissatisfaction, anguish, pain, suffering.' We will be determined and will diligently engage in the methods of practice to attain liberation if we are no longer enticed by delusory worldly pleasures. And so, the first step is seeing the need to give rise to the wish to become free. Having realized the necessity of giving rise to the wish for liberation, the second step is seeking and knowing the method to do this. Tsongkapa instructs us in the next verse.

b) Arousing the Right Wish for Liberation

/ däl-'byor-rnged-dka-tshe-la-long-med-pa /

/ yid-la-goms-päs-tshe-'di'i-snang-shäs-ldog //

'Don't waste (your) precious human life that is so difficult to find, but become accustomed to reversing (your) attachment to pleasures of this life."

In this verse, Tsongkapa inspires us to arouse the right wish for liberation. We do this by understanding that, just like most living beings in the world, we are accustomed to only seeing any bad luck or unfortunate and unsatisfactory situation that we experience as suffering. We consider the moments or periods of time when we aren't suffering as pleasant. It's needless to say that it's natural that nobody wants to suffer. Being willing and making use of the opportunity to directly look at our wish to be free of suffering when we feel pain or suffer enable us to realize that the pleasant moments we experience between moments of feeling pain change and again manifest as suffering. Realizing this, we understand that pleasant experiences of happiness are actually 'gyur-ba'i-sdug-bsngäl, 'suffering of change.' Our happiness that we cannot hold on to or keep is in fact suffering that we experience due to change. We understand why the Buddha taught the truth of suffering. He directed our attention to our fundamental drive to want to be free of misery and suffering when he taught us to realize that pleasure changes and therefore entails suffering when he turned the Wheel of Dharma the first time and spoke about the Four Noble Truths. Having understood the first two kinds of suffering, we can then understand that all conditioned existents are permeated by khyab-pa-'du-byed-kyi-sdug-bsngäl, 'all-pervading suffering of conditionality.' Those are the three kinds of suffering or problems that the Buddha spoke about and explained.

Since understanding the truth of suffering gives us the incentive to arouse the wish to attain liberation, the Buddha taught about suffering when he presented the teachings on the Four Noble Truths at Sarnath in India. When he taught the First Noble Truth, he stressed the importance of knowing suffering and said, "Suffering and pain should be identified and known." He wasn't referring to the direct suffering that living beings feel when they are hurt, because everyone experiences pain like that on their own and needn't be told about it. Rather, the Buddha said that we should recognize suffering as suffering before it arises and we should know that the suffering we normally don't recognize is in fact suffering.

Looking at our life, we have three kinds of feelings. When we feel pain, we suffer. Furthermore, we experience some things as pleasant and nice and are neutral or indifferent about other things that we perceive and experience. It's not astonishing to consider that physical or mental pain is suffering, but we won't have the right wish to attain liberation if we only think that having this kind of pain is suffering. Having the right wish to attain liberation can only be born in our mind if we recognize suffering in our pleasant feelings and in our feelings of indifference. And that is what the Buddha meant when he taught that we should recognize and identify suffering as suffering. How do we do this?

Presently, we identify unpleasant feelings as suffering and strive to eliminate them. Not aware that pleasant feelings and indifference also entail suffering, we long to always experience them and become addicted to our "wanting," i.e., to our longing to be happy. It doesn't function, though. For example, we feel uncomfortable when it's very hot outside and, yearning for refreshment, we jump into the swimming pool. Having stayed in the cold water for a while, we feel comfortable and think that the source of our satisfaction is the swimming pool. But we feel chilled and start shivering with cold if we stay in the water too long; then we feel dissatisfied again and yearn for warmth. We get out of the water, sit at the edge of the pool, and let the sun warm us. Having become warm, we feel satisfied and think that the sun is the source of our satisfaction. Depending on our feeling, we see either the sun or the pool as the source of our satisfaction and strive to experience the one or the other, without understanding and wanting to admit that passing happiness isn't really true happiness. The moment we jump into the pool, we don't see that the water in the pool isn't the source of lasting happiness, but is the cause for us to subsequently suffer from cold. The moment we get out of the pool and take a sunbath, we don't see that the sun isn't the source of lasting happiness, but is the subsequent cause for us to suffer from heat. We don't realize that the sun and the pool aren't the source of true satisfaction, comfort, and ease, but are sdug-bsngäl-gyi-sdug-bsngäl, 'suffering of suffering.'

Identifying suffering as suffering means recognizing that the source of assumed happiness and satisfaction isn't different than the source of suffering. Recognizing and identifying suffering as suffering means not mistaking, but knowing that we can't hold on to the passing happiness and comfort we feel, for example, when we are either in the swimming pool or in the sun, and that our satisfaction in the one situation or the other isn't true happiness and joy. Being free of the delusion as to the source of our satisfaction and happiness, we recognize suffering in the change that incessantly takes place. Not wanting or refusing to see this, our attitude and outlook is called "blindness," i.e., we blindly crave for and chase after whatever we happen to think is the source of happiness. If we have understood this principle in a few cases, then we can apply it to every other situation in life. By understanding that we can't hold on to a pleasant feeling we have because it is impermanent, we realized that in truth it is suffering.

Let's look at the example of a meal that we have and think is delicious. We enjoy the tasty food and are really happy when we have it. But if we keep on eating and eating, our pleasure of eating the tasty food gives us a stomach ache. And so, the suffering of change has once again become evident. If our belief were justified that the meal is the source of pleasure, our pleasure would increase more and more and as long as we continue eating and eating, but this isn't the case. If the refreshing water in the swimming pool were the true source of pleasure and joy, then we would feel happier and happier the longer we stay in the pool, but this isn't the case. If the warmth of the sun were the true source of happiness, then we would feel more and more satisfied the longer we sit in the sun, but this isn't the case either. The point is realizing that pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral feelings connote suffering.

Why does a feeling seem pleasant? Only because we have a momentary unpleasant feeling. Whatever we consider pleasant reverses our feeling of dissatisfaction. Other than that, there's no valid basis to label our feeling of happiness or pleasure. For example, we scratch an itch that annoys us, but we would never think that scratching brings pleasure. We merely feel relieved of the pain of an itch when we scratch it. We wouldn't think that our hand is the source of our pleasure when we use it to scratch an itch. Rather, it's due to the insufficiency of an itch, i.e., its inability to make us feel content, that we are able to feel good by scratching it. This applies to other things, too. The water in the pool we jump into isn't the source of our pleasant feeling of being cooled on a hot summer day, rather, it's due to the sun's inability to make us feel happy that we are able to feel good by taking a dip in the pool.

In life, instead of seeing the insufficiency of a foregoing event, we make the mistake of thinking that the new and subsequent solution to an unpleasant feeling is the source of our happiness and pleasure. In our example, why do we feel that the water in the pool is refreshing? Because we suffered from the heat of the high sun and feel good by the subsequent cool water in the pool. When we suffer a chill by staying in the cold water too long, we feel satisfied by subsequently sitting in the sun. So, any pleasant worldly experience is the subsequent pleasant feeling of having experienced the insufficiency of a foregoing event. For example, we are content after we quenched our thirst or stilled our hunger. It wasn't the drink or food that caused us to feel pleased, rather, it was the momentary suffering of hunger and thirst that caused us to feel happy after having had food and drink.

We are used to assuming that worldly pleasures only result from the things that relieve us of out various physical shortcomings. The more we think that outer things are responsible for our feelings of pleasure and the more we are addicted to them, the more we distance ourselves from the source of true and reliable happiness and well-being. It's like drinking salt water; the more we drink, the thirstier we will become and thus we distance ourselves more and more from reliably quenching our thirst. Knowing that it's not the qualities of our fingers that relieve us of the pain of an itch, the wish to reliably rid ourselves of the itching pain will be born in our mind. If we think our hand is the source of ridding ourselves of the agony of an itch, we will continue scratching it and will only perpetuate more suffering and pain. So the joy we feel of treating our pain by scratching an itch that we have is delusory. When we realize this, we will seek reliable treatment by consulting a physician. Having understood this, we also won't think that food and drink are qualities of being for us. Instead, we will realize that thinking they are the source of satisfaction results from our hunger and thirst. Knowing this enables us to more easily understand that eating and drinking are delusory pleasures and thus we will seek reliable means to become free of our hunger and thirst.

With this in mind, we can see the Buddha's physical appearance differently and can understand that he was free of the suffering of hunger, thirst, heat, and cold. Then we realize that any suffering of hunger, thirst, heat, or cold that we experience is not our true nature, but that these feelings are passing feelings of suffering and pain that we have because of being deluded. Since we are endowed with the same qualities as the Buddha, we aren't destined to suffer, but to be free of suffering.

By recollecting our day in the evening, we recognize that the moments we experienced pleasant and unpleasant feelings continually alternated and we recognize that any feeling we had was not substantial and didn't last. We realize that it wasn't the water's fault that we were chilled when we stayed in the swimming pool too long, but that it was due to having been affected by the heat of the high sun that changed into the suffering of feeling cold while in the pool. All alternating pleasant and unpleasant feelings are due to impermanence.

We might understand this and conclude, "Okay, I realize that I helped myself when unpleasant feelings arose and changed, and I tried my best to get through. Days and years pass and one day I'll die. Then I won't be hungry and thirsty and won't suffer from heat and cold anymore. Why all this talk? I managed quite well. I was intelligent and turned on the heater when it was cold, took a swim in the pool when it was hot, ate when I was hungry, and had a drink when I was thirsty. What's the problem?" We should know whether there's a problem or not. If there's no problem, this seminar is finished.

The Buddha spoke about impermanence and death to help us overcome our delusion. Dying occurs due to impermanence, which culminates at death. If death were the end, then our decision to just live through the day as best as possible would be justified and our efforts to eliminate our unpleasant feelings of hunger, thirst, heat, and cold would end when we die. Then there would be no problem. But if it's not like that, if not everything ends when we die, but new appearances emerge at that time, we would have to reconsider the matter. The Buddha taught that death isn't just the end of this life, but that it's the beginning of a new life. Our body becomes a corpse when we die. Our mind doesn't turn into a corpse when we die, though, rather, our mind gives rise to new appearances that lead to a next life after we have died. By acknowledging that death isn't total annihilation, like a table that has burned to ashes, we appreciate that it is the beginning of another new appearance. When we understand that this life isn't the last one we have, we realize that it isn't the first one either. We understand that our present life began when our last life ended. And so, life and death are a continual process of living and dying and of being in the world.

Knowing that a past life led to this life, it's conclusive that there's a next life. We try to understand if it's like this by asking, "Did I have a last life and will I have a next life?" We can logically deduce the answer by examining the present moment of our mind, our consciousness. Looking at the present moment of our mind, we investigate by asking, "How did it arise? Did it arise on account of my body?" If we investigated and know that the present moment of our mind did not arise from our physical body and understand that it arose from the previous fraction of an instant of our mind, then it's logical that the last millisecond of our mind arose from a previous tiny fraction of an instant. If we follow this process back, we arrive at the moment we were conceived. Thinking the process through, we realize that the moment we were conceived wasn't the beginning of our mind. Since our mind arises from a previous moment of mind, then it's logical that our mind cannot have been created by our body, but from a previous moment of mind that existed before we were conceived. This isn't saying that the present state of our mind doesn't depend on our body. There's no doubt that it does and that it is influenced by our body. The question is whether our mind can arise from our body, i.e., can our mind be newly created from our body? That's the question.

If our mind originates from our body, the qualities of our mind would increase when our body grows and decrease when our body becomes weak. But, as we know, this doesn't happen. For example, while developing the qualities of our mind by being absorbed in the study of a new topic of interest, it does happen that we forget to eat and lose weight. This shows that our mind's capacity doesn't depend on our physical strength. How, then, does our mind originate? Looking at a fruit tree, for example, it grows from a fruit tree sapling and ripens into a fruit tree if it is provided with the necessary conditions. In comparison, can physical matter create mind? If not, where does mind come from? Just like matter arises from matter and not from mind, mind can only originate from mind. So, our present state of mind must have arisen from a previous state of mind and not from physical matter; and the previous state of our mind must have originated from a former state of our mind, and so forth, i.e., mind arises from mind. This means to say that the first moment of our mind in this life has to have originated from a previous moment of mind.

If we investigated well and know that our present state of wakeful awareness (sems, i.e., mind or consciousness) cannot have arisen from dead matter, but originated from our previous state of wakeful awareness, it's logical and conclusive that our previous state of wakeful awareness originated from a former state of wakeful awareness. In this way, we have clarified that our present life isn't our first life, but originated from a last life, and that this life isn't our last life, but that we will have a next life. Since our mind doesn't originate from matter and our present mind is the continuation of previous moments of mind, our mind doesn't come to an end when our body ceases to be. Rather, after the death of our physical body, a next moment of consciousness follows.

Again, mind (sems) gives rise to mind (sems) in every moment of time, i.e., consciousness is born from consciousness. In other words, wakeful awareness arises from a previous moment of wakeful awareness. We see this through the power of habituation, of familiarization, of learning. Taking the Tibetan text I'm holding in my hands, it's only meaningful for people who can read Tibetan. Those persons who know Tibetan can read it and might understand what they are reading. Their understanding was not born from the signs on the paper, but from previously having become familiar with the script and the language, which goes back to former moments of having become familiar with the script and the language. Merely looking at the text doesn't enable us to enjoy reading and understanding the contents. Our present knowledge of a topic originated from having formerly become familiar with the topic. It's a long story that started at one point in our life. We received instructions from teachers and people we associated with, were nourished by our parents during that time, and were supported by our friends, just to name a few supportive conditions. Our present knowledge of a specific topic is the result of many previous moments in which we became familiar with the ability to understand this topic. If we go back to the beginning or early part of our present life, we will see that one moment of familiarization followed upon another. These reflections show us that body and mind are different.

Our body has a form, has a color, can be measured, while our wakeful mind has no form, no color, and can't be measured. Our mind isn't a tangible object, can't be seen, isn't limited, and can't be restricted or impeded. If we investigate the difference between our body and mind closely, we will easily understand that neither our physical limitations or our physical death restrict our mind. We experience this every night when we sleep and when we dream. If we understand that while our body rests in sleep our mind is very active and vibrant during the dreaming stage of sleep, we understand that our mind doesn't end when our body has ceased to be. Therefore, death doesn't mean that both our body and mind come to an end when we die, rather, death is the separation of our mind from our body " it's the time the guest leaves the guesthouse.

Why are these instructions very important? So that we understand that life precedes life and is followed by life. If we acknowledge past and future lives, we will be able to understand that all our actions give rise to results and that our present situation is the result of our previous karma, 'actions' (läs in Tibetan). Understanding karma enables us to better understand that suffering marks conditioned existence. If you have any questions, please ask.

Question: "It's logical for me to think that the mind I have now is the mind I always had, but the mind I have now isn't the same as the one I had as a newborn. The deductive process is shattered when I say that mind is created from matter at the moment of conception or is born from a nebulous unconscious state."

Drupön Khenpo: Looking at one part of your question, that mind could have arisen from matter, the question is, from which matter? Do you think mind arose from the father's seed and mother's ovum?

Same student: "Matter has to be defined. It's also said to be energy and the seed is also a form of energy."

Christoph (our translator): "Now your question implies that the seed and ovum of the father and mother are connected with their mind."

Drupön Khenpo: If this were the case, the child would have to be like the father, i.e., if the father is very intelligent and good, his child would be very intelligent and good and if the father is evil, his child would be evil. The child wouldn't need to go to school if the father is very intelligent, because his intelligence would flow into the child through his seed.

Same student: "That's not logical for explaining what is new, because the logic would be that it is a combination of both father and mother. It is the one and the other."

Drupön Khenpo: In that case, if both father and mother are very intelligent, then their child would be double-intelligent, i.e., the child would have the qualities of both parents. It's difficult.

Same student: "It's not difficult for me. It's a matter of combination. From a mathematical point of view, it can, but doesn't have to be like that. I brought in the argument that the present mind doesn't arise from the previous moment of mind because I don't have the mind that I had when I was a child. Therefore, the same question arises for the parents. Thinking logically, not all genetic attributes manifest."

Christoph: "You mean to say that a moment of mind would be a package of all qualities, i.e., a moment isn't singular, but multiple. Is that what you want to say?"

Same student: "Yes."

Drupon Khenpo: It's difficult comprehending the process of how our mind arises because our mind consists of the habitual patterns that are created from many consciousnesses, for example, the five sense consciousnesses. How would it be possible for the five sense consciousnesses to arise from the mere presence of an ovum and seed, i.e., dead matter?

Same student: "That's what I meant. If we follow it back to matter, there is a point where there is no matter, but only energy. And this energy is contained in the matrix. But the matrix has neither mind nor matter, but is another form. And mind can arise from this other form, from the information contained in matter."

Christoph: "A basic state that contains both mind and matter?"

Same student: "Yes, information as mind. Mind as we have it is relative, because my mind isn't the same as it was when I was a child."

Christoph: "So, you purport that there is a basic state or substance of matter that contains and creates both mind and matter?"

Same student: "Yes."

Drupon Khenpo: Considering the fact that our mind isn't the same as it was when we were young, you argue that it could arise from something that is different than mind. That is your question now, right?

Same student: "Yes."

Drupon Khenpo: That is where you might have misunderstood the teachings. I didn't say that our present mind is identical with the mind we had as a child, rather, that our present moment of consciousness arises from our previous moment of consciousness. For example, our ability to read and comprehend the meaning of the sequence of letters printed in a newspaper wasn't born the moment we looked at the newspaper, but is based on the fact that we became familiarized with reading and understanding what we looked at and read. Our familiarization manifests in a present moment and also manifested in the previous moment of our mind. This means to say that our familiarization of certain things increases. A child hasn't become familiarized with the ability to read and understand a newspaper, but it became more and more familiarized as it grew up and learned. This doesn't mean that there was no starting-point in the life of a child, because, without having had to learn and without erring, a newborn directly grabs for its mother's breast. If we trace the process back, of becoming as familiar with things as we are now, we reach a point that makes us believe that mind arose out of matter, or out of nothing, or haphazardly. If we assume that the one or the other assumption is right, the chain of familiarization would end there. The discussion in this seminar is that every moment of familiarization is based on the previous moment of familiarization and also leads to the next.

c) Reversing Attachment to Pleasures of Conditioned Existence

/ läs-'bräs-mi-bslu-'khor-ba'i-sdug-bsngäl-rnams /

/ yang-yang-bsam-na-phyi-ma'i-snang-shäs-ldog //

'Again and again reflecting that samsara's suffering is the inevitable fruit of actions reverses craving and attachment to subsequent pleasures.'

Being aware of the fortunate situation of having a precious human birth, contemplating impermanence and death is the first method of the path to arouse the wish for liberation. The second method is being aware of the purpose of giving rise to the wish for liberation by contemplating the consequences of our actions, i.e., karma. Acknowledging karma is based on realizing that everything in the world is impermanent and on accepting that we had past lives and will have future lives. Contemplating in this way encourages us to give rise to the wish for liberation.

We can't prove the law of karma or the existence of past and future lives that result from karma by means of deduction, because they aren't objects of knowledge that can be known through rational cognition. These truths are hidden, i.e., they can only be known by means of indications. What is referred to as "extremely hidden" can only be known by a fully enlightened One, a Buddha, who possesses direct insight of past and future lives and of karma. Therefore, we can only appreciate and acknowledge karma and past and future lives by trusting the words of the Buddha. Because they can't be refuted or proven by means of analytical reasoning, without the words of the Buddha we wouldn't know about karma or about past and future lives.

There are three kinds of knowledge that we can acquire. They are: direct perception, indirect cognition, and extremely hidden knowledge, which can't be cognized by means of direct or indirect cognizance. Objects of the senses are perceived directly, so we don't have to resort to analytical reasoning to prove that we perceive them. Hidden objects can't be known directly. For example, ordinary beings don't directly understand impermanence (the transient nature of all things), emptiness (the lack of substantial and inherent existence of all things), and so forth; ordinary beings have to rely on indications to know them, which is what indirect cognition means. Extremely hidden knowledge means knowing that good actions result in pleasure (even in the great satisfaction and happiness that beings living in the god realms experience) and that bad actions result in suffering (especially in the great suffering that beings living in hell realms experience). We can't perceive the realms of the gods or hell beings nor deduce their existence and therefore they are also extremely hidden. Knowledge of karma is also an extremely hidden object of knowledge that we are able to think is plausible. By relying on the words of the Buddha, we can appreciate and acknowledge the law of karma. If we trust the Buddha's words about past and future lives and about karma, we can use our reasoning and examine in which way cause and result apply.

We believe the words of the Buddha, who teaches us that our actions have specific results that only a Buddha can know. But we can examine whether phenomena arise from self, other, both of them, or without a cause. By observing things in the world, we realize that nothing occurs haphazardly, but that there is always a related cause that gives rise to a corresponding result. We will never find that something is born from a cause totally different from it, rather, that things always arise from a related cause and specific conditions.

If we apply our general observation of things in the world to our mind, we will understand that our mind cannot arise from something that is totally different or other than it, i.e., from something that is not mind, but that our mind arises from a related cause. Since every moment of our mind arises from the foregoing moment of our mind, we can trace it back to the time our mind first entered our body. But we need to clarify how this first moment of mind in our body arose to understand that a former moment of mind always precedes and is followed by a later. Having understood that every result has a related cause, we realize that the first moment our mind entered our body was preceded by a cause that was related to the result, i.e., a moment of mind. This way we realize that our mind didn't arise suddenly when we were conceived, but that our mind is a continuation of our mind. This leads us back to a former life, because, as we saw, whenever there is a former cause, there's always a later result, which in turn becomes a cause for a following result. Therefore, if we observe occurrences in the world and compare them with the continuation of our mind from one moment to the next, we can understand that we had a past life and will have a next life.

There are many ways to reflect whether we had a previous life and in which form. It would be wonderful to speak about all of them in detail, but we don't have the time during this seminar. We can believe the Buddha who tells us that all of us had many lives and we can look at the advantages of believing him. By believing him, we extend our faith in the Buddha, yet, we can't come to a knowledgeable conclusion by simply believing what the Buddha said. By merely believing him, we can't come to a harmonious agreement with everything that can be known and then we have difficulties integrating his words in our life. Some people remember events from their past life and speak about them. It's only possible for them to remember those events because they experienced them, which is also evidence that we had a past life.

We can notice that most of us and the people we know have what it takes to become aggravated, to be greedy, to be ignorant or dull-witted, also to be proud and jealous. Usually we had to be trained and received an education to learn what we know and to have the capabilities that we have, but we have those traits without having had to learn them in this life. Since we can feel aggravated, be greedy, and be dumb, we must have become familiar with these traits in the past, otherwise it would be quite difficult to explain why we have them. Somebody could argue, "Okay, aggravation, greed, and ignorance are our nature, so we didn't have to learn them. These emotions are our nature, just like heat is the nature of fire. It's not possible to remove heat from fire. If it were possible, fire wouldn't be fire." Should we think that our conflicting emotions are just as much our nature as heat is the nature of fire, any attempt to remove them would be in vain and it would be impossible to ever become free of aggravation, greed, ignorance, and our other conflicting emotions.

An example for our body is a computer and the programs. Our computer would be useless without programs. The first moment of conception can be compared to a computer. It slowly uploads the programs after we turned it on. Uploading our computer can be compared to the time our body slowly grows through the care of our mother as well as other conditions. Aggravation, greed, ignorance, and the many conflicting emotions are present, but aren't evident when we were conceived; they start manifesting and become apparent when we start speaking. They weren't absent when we were conceived and took birth, just like the programs installed in our computer aren't missing when our computer is switched off and don't need to be installed anew every time it is switched on. The programs need to have been installed earlier so that our computer functions when we want to use it. In that way, claiming that our conflicting emotions arise suddenly, or on their own, or by chance, or without a cause can't stand the test. We have to have become accustomed to the conflicting emotions that we have for them to be present and for them to appear when specific conditions prevail.

Looking at our mind, we see that it has qualities of wakeful awareness. When we investigate, we usually don't make a distinction between mind and matter. The conventional ways of thinking are that mind is born from the combination of the five elements (earth, water, fire, air, and space), or from the connection of the seed of the father with the ovum of the mother, or of its own accord, or suddenly in material objects like stones, wood, and so forth. We can argue, "No, it's not that simple. Not just any material substance can create mind, because mind is created from a father's and a mother's mind and substances." Knowing that our father and mother have a mind causes us to think like this. In that case, we could ask, "What is the relationship between our father's seed and his mind and our mother's ovum and her mind? Are their minds their seed and ovum or are they mixed? Or does mind have the quality of matter that is inside the seed and ovum?" We can investigate further and ask questions like, "Why is this only the case for a seed and ovum? Do the parents' minds weaken and diminish when they render their seed and ovum to give birth to our mind? Why don't the limbs or physical organs of the parents have a mind?" We would have to examine and analyze all these complex possibilities if we think that there's no difference between mind and matter. Many complex assumptions come up when attempting to explain how a mind enters a body, and everyone can continue investigating as they please. We are free to think of it in less complicating ways by trusting and coming to know that our mind is our own continuum that arises from foregoing moments of our mind. Seeing it in this light is the basis for believing in past and future lives and for appreciating and accepting the law of karma, i.e., that our experiences originate from our own actions.

These reflections seem meaningless to somebody who thinks, "Fine if it's like that. Since the one thing arises from the other and my past life led to this one, I'll just go along with it. Why worry? What difference does it make?" Should there be only one kind of rebirth, there would be no reason to worry. But there are many kinds of existence. Rebirth is possible in pleasant and unpleasant states of existence, such as in one of the realms of the gods, in the realm of the jealous gods, as a human being, as a tormented animal, as a hungry ghost whose thirst and hunger is never stilled, or in one of the hell realms. That's why we contemplate these instructions. It wouldn't be a serious matter if our next life merely depended on our wish to have a pleasant next life, but the Buddha tells us that our actions determine in which of the six realms of existence we will be born. He taught that malevolent actions that we carry out and that hurt others cause us to be born in an unpleasant realm that is marked by suffering and pain and that benevolent actions that we carry out and that benefit others cause us to be born in a pleasant realm of existence, e.g., as a god or as a human being.

It doesn't suffice to just hear the Buddha's teachings, that a pleasant life is the result of having engaged in virtuous deeds and that an unpleasant life is the result of having engaged in non-virtuous actions. It's necessary to contemplate these teachings well and to manifest, i.e., to live, the fruits of having understood them. Yet, we won't be able to contemplate these instructions if we haven't heard or received them. The purpose of contemplating the teachings we have received is to know, for example, that we have to plant rice seedlings and not wheat seedlings if we want to have rice. Since we know that everything that arises and develops has a related cause and since we wish to have a pleasant life, we know that we can only have a good life if we engage in virtuous actions and refrain from engaging in non-virtuous actions. We know that nothing arises due to anything foreign to it or due to not being connected with a related cause, rather, that related causes give rise to corresponding results. Having contemplated and observed that everything arises from a related cause and depends on it, we gladly engage in beneficial activities (läs-dge-ba) that cause happiness and well-being (bde-ba) and gladly refrain from engaging in non-virtuous actions (läs-mi-dge-ba) that cause suffering (sdug-bsngäl).

If we look at the fundamental relationship between cause and effect (rgyu-dang-'bräs-bu), we understand that our pleasant and unpleasant experiences are the result of the benevolent and malevolent activities of our body, speech, and mind. We interact with others in dependence on our mind (i.e., our thoughts and intentions) and act by means of our body and speech. Verbal and physical activities aren't good or bad as such, rather, our thoughts move us to speak and act the way we do. Our thoughts are our driving force. Beneficial and harmful actions are based on our motivation, therefore we have to distinguish between beneficial and malevolent intentions. When we understand this, then we realize that some actions that we carried out are beneficial and good and some actions that we carried out are harmful and bad. But, how do we know whether we have a good or bad intention?

Bad intentions are thoughts of ill-will that are determined by attachment, 'död-chags. There's a great variety of ways to be attached and they can be subsumed in three categories. The three categories of attachment are aggravation, greed, and ignorance or unawareness, ma-rig-pa. There's no need to discuss that any action carried out due to aggravation is bad and leads to painful results. But, why do actions based on greed and ignorance lead to unpleasant results? Let's look at ignorance first. There are two kinds. One is here and now not realizing the true nature of reality. Having this kind of fundamental ignorance can't be said to be either beneficial or harmful; depending on conditions, its results are indefinite. The other kind of ignorance is the inability to recognize the law of cause and effect. Failing to recognize the connection between cause and effect is harmful. The same pertains to greed.

There are different ways of being greedy. One way is being greedy for objects directly perceived with the sense faculties, i.e., craving for pleasures for this life. Greed of this sort is harmful and bad because it causes us to neglect the results of our actions and to ignore long-term perspectives. Somebody might conclude, "Fine, I understand that there are past and future lives and that good actions lead to good results, so why shouldn't I do good and establish a mindset for myself that enables me to attain a life that is just as exquisite as that of a universal monarch?" Such an intention is directed towards a long-term perspective, a next life and not this life, nevertheless, it's craving to be born within the rounds of conditioned existence. Since it's uncertain whether this kind of greed will lead to a good or bad result, it's indefinite. Having greed of this kind can' be said to be harmful, because knowing that good actions lead to a good birth inspires an individual with such far-fetching ambitions to do good. Yet, the intention is based on greed and the result is transient, unstable, and illusory. Any good that is achieved by striving to have such a high rebirth is subject to loss. Such an individual can attain a good next birth, the only problem is that it's unstable, entails eventual loss, and thus leads to suffering. Seen more deeply and subtly, anybody who does what is possible to attain a better birth and could direct his intention on attaining liberation. Wishing to attain a good next life and not liberation is described as having an inferior motivation.

So, there's a difference between our fundamental tendency to be ignorant and greedy. There is ignorance and greed that bring definite harm and there is ignorance and greed that lead to an indefinite result, e.g., our fundamental inability to directly recognize reality the way it is. This fundamental ignorance needn't lead to harmful results. Even though most people have this fundamental ignorance, they can do good by engaging in beneficial activities. The same for greed. The joy of wanting to attain a good rebirth for oneself by engaging in beneficial activities is good, but it is transient, unstable, and illusory. It isn't bad, but it's unstable because there is the possibility and likelihood of again becoming involved in harmful activities. It would be more becoming for such a person to think, "Yes, I want to become free from the cycle of suffering and will practice the path to attain liberation for myself."

What are negative intentions and desires? Next to ignoring and neglecting any perspectives other than enjoying life, a negative intention arises from ignorance or mental dullness of not wanting and therefore not being able see the results of own actions. We can say that there's a harmful aspect of being ignorant of past and future lives in that such persons don't see the necessity and purpose of engaging in what is beneficial and good; therefore they don't make best use of their life. So, being ignorant of the nature of reality, concentrating on attaining a good future life by doing good in this life, and having the wish to attain liberation for oneself aren't bad. But we should look at the reason such intentions lead to suffering.

We can know which actions cause suffering by looking at the laws of the country we live in. Actions that are in discord with the rules of a country are illegal and punishable by law and those that are in accord with the rules of a country are supported and honoured by the societies we live in. Therefore, good and bad actions are general rules about bringing happiness to others or causing others suffering and pain. Bad actions are the same as illegal actions and lead to experiencing the unpleasant consequences when punished by law.

It would be helpful to distinguish the four ways of clinging to better understand what good and bad actions are. The four ways of clinging are: clinging to worldly things; clinging to the wish to benefit oneself; clinging to attaining a good next life; and clinging to the pleasures of this life. All four ways of clinging are harmful and each leads to a different degree of negative results. For example, the other three ways of clinging are included if we cling to the pleasures of this life. If we are free of craving for pleasures of this life, we aren't automatically free of the other three. Therefore, the four ways of clinging are differentiated from coarse to more subtle. In short, the four ways of clinging don't harmonize with the interrelated connectedness of things and lead to different degrees of suffering. For example, we would be living 100 percent in opposition to the interrelated connectedness of things if we only strive to attain pleasures for our life and would experience 100 percent suffering as a result. Should we wish to become free of such craving, we would need to contemplate the transitory nature of all things. Having done so, we would realize that everything pleasant that we want to have now is impermanent. Knowing that having pleasures in this life isn't reliable, we automatically wish to create the conditions for a good next life and thus engage in good activities. Our actions will then be 25 percent in accord and 75 percent in discord with the connectedness of things. By dispelling hindrances and misconceptions, our ability to do good grows and our discordant actions diminish.

Now we have a better understanding of the relationship between harmful actions that evolve out of ignoring and denying the law of karma, i.e., that every cause leads to a corresponding result, which includes wanting to have pleasures for this life only as well as aggravation. These three factors belong together. We know that bad actions, which are carried out due to antipathy and resentment, cause suffering. How does aggravation arise? It arises from craving for pleasures in this life and feeling upset and irritated when anything impedes us from fulfilling our wish. If we didn't crave for things, we wouldn't have a reason to feel aggravated or upset when things go wrong. Why do we crave for and cling to things for this life? We think that only this life is important and worth living for. So, the cause of clinging to pleasant things in this life is lacking knowledge of former and future lives and denying the results of own actions. Why are greed and ignorance harmful? Because they pave the way for us to cause harm by feeling aggravated and angry about anything we think gets in our way. The other emotions, such as pride and jealousy, are also based on craving for a pleasant life.

In other words, ignoring former and later lives and denying the results of own actions stands 100 percent in opposition to the interconnected relationship between things. It causes 100 percent suffering that is a result of craving and being greedy for the direct experience of pleasant things in this life. Aggravation, anger, jealousy, pride, and the other conflicting emotions are born from craving for pleasant things in this life and evolve into actions of body, speech, and mind. This was a description of how bad actions, which are harmful and are defects, are born.

We have looked at the difference between beneficial and harmful actions. We saw that there are indefinite actions of body, speech, and mind. Actions have related harmful results, related beneficial results, or indefinite results, which means that it's uncertain whether the result of an action will be beneficial or harmful. We also looked at virtuous and non-virtuous actions of body, speech, and mind and saw that they are based on desire, which is determined by ignorance, or greed, or aggravation, or all three.

Looking at good actions now, they are based on good intentions. A good motivation or intention is characterized by being free of ignorance, greed, or aggravation and means having the opposite qualities of these negativities. As was the case for negative actions, for an action to be good means knowing that something precedes what follows and acknowledging and accepting the law of karma. Craving for pleasant things in this life isn't our goal when we have good intentions. Being free of wanting to have everything pleasant in this life and thus being free of craving and greed, we aren't aggravated by hindrances that would otherwise upset us. Furthermore, being free of ignorance, greed, and aggravation ensures that our verbal, and physical actions will be wholesome and good. We saw that we become familiarized with thoughts and actions that we carry out and that they become habits. Even after we have died, our habits that have become lodged in us manifest to us as new appearances, which are related with the habits we accumulated.

The motivation makes the difference between good and bad actions. Our actions occur in reciprocity with our environment and the world. Our actions also depend on conditions, which are our body, our possessions, our friends, relations, and living beings in the world. It's necessary to differentiate between causes and conditions. Our body isn't good or bad, rather, our intentions determine whether we make good use of our body or not. The same with our possessions; they aren't good or bad, rather, our intentions determine whether we use them for a good purpose or not. It's the same with our friends, enemies, and associates; our relationship with them determines whether we act good or badly. These three - our body, possessions, and the people we associate with " aren't good or bad as such, rather, they are the contributory conditions that cause us to act virtuously or non-virtuously. If we mentally, physically, and verbally relate to these three contributory conditions harmoniously and in mutual accord, beneficial results will follow; if we do so in discordance, unpleasant results will follow. In other words, if we relate to the three contributory conditions free of ignorance, greed, and aggravation, then pleasant results will ensue; if we relate to them with ignorance, greed, and aggravation, then unpleasant results will ensue. So, by ignoring former and later lives and by denying that related causes engender corresponding results, we will crave for and cling to our body, possessions, and people and will be dissatisfied, have problems, and have other negative emotions when negative conditions prevail.