Finding Peace in Troubled Times

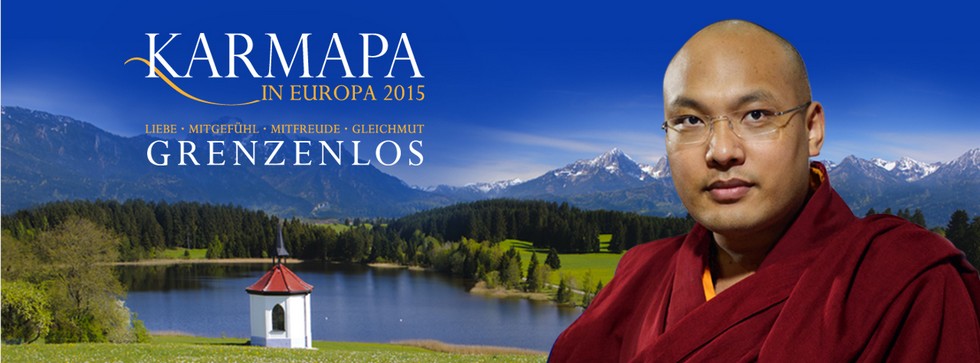

Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

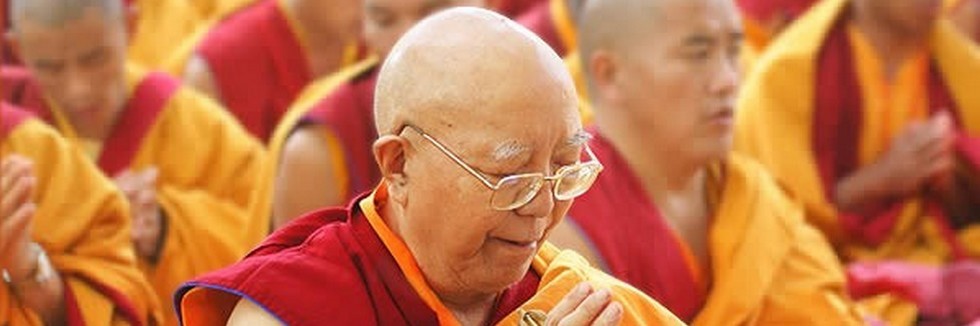

At this time, following the earthquake that completely destroyed Thrangu Tashi Chöling in Jyekundo on April 14, 2010, we would like to dedicate any merit that arises from this article to most Venerable Lodrö Nyima Rinpoche, the nephew of Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche, Abbot of Karma Triyana Dharmachakra in N.Y.

In 1992 His Eminence Tai Situ Rinpoche recognized Karma Lodrö Nyima Rinpoche as the 9th reincarnation of Bengar Jampä Zangpo, the well-known composer of 'Dorje- 'Chang Thung-ma 'The Short Dorje Chang Lineage Prayer. ' Having completed the traditional three-year retreat in the retreat center at Thrangu Monastery in Tibet, Lodrö Nyima Rinpoche has resided there ever since and is the monastery head. Through his tireless and selfless activities, he had transformed the monastic community into a flourishing Dharma center for both the Lamas and village people. He established a Shedra for the monks, restored the old monastery, built a beautiful new one, rebuilt the retreat center that houses the precious Kudung of the Very Venerable Kyentse Ösä Rabsä, the Second Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche. Last year, he also finished building an Ani Gompa not far from the main monastery. Our prayers also go out to the many victims of the earthquake.

View of Thrangu Tashi Chöling from the hilltop.

At the inauguration ceremony of the new Gompa, which was sponsored by Karma Yeshe Chödzong Jamgon Kongtrul Foundation in Canada, the Very Venerable Lodrö Nyima Rinpoche offered the officiating speech to over 20,000 people and presided over the festivities.

Tibetan village people offering Kathaks on the opening day of the new Gompa, July 2004.

Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

Let me greet you kindly and ask that we recite the Dorje- 'Chang Thung-ma 'The Short Dorje Chang Lineage Prayer before beginning the teachings. It is said in many instructions that all accomplishments really come from practice. It's because of practice that one is able to receive the blessings of the Lineage and can develop the power of the practice. However, attaining the power of the practice depends upon one's diligence, which in turn depends upon one's faith and devotion. So, in order to develop faith and devotion that are necessary when aspiring to practice the Dharma, one needs to do the preliminary practices, which are called Ngöndro in Tibetan.

When engaging in the actual practices of tranquillity and insight meditation, deep concentration is primary because insight needs to have a basis. The basis for meditative concentration of insight is tranquillity meditation. It's important that one has a good, stable, and resting aspect of tranquillity. Since this is important, one first does the practice of tranquillity meditation.

In the instructions on tranquillity meditation, there are the points for the body and the points for the mind. Of these two, the first one is the points for the body, which are usually described as the 'Seven Points of Posture of Vairocana. ' Sometimes it isn't possible to sit comfortably in this posture. If one can sit comfortably in the seven points of Vairocana, then one should. But if one can't, it's okay 'it's not absolutely necessary. What's said to be most important is to sit in a way that is comfortable and relaxed, in a way that is not too tight. It is said that it's important not to tighten, hold, or push oneself too much, rather, to sit in a comfortable, relaxed, and easy way.

Whether sitting in the seven-point posture of Vairocana or not, it's important that one is comfortable. This was described by the great teacher Machig Labdron, who brought the pacification teachings called Chöd to Tibet from India in the 11th century. She taught that the points of the body are the four channels that run through the four limbs of the arms and legs and instructed that they should be loose and relaxed and that one should not tighten them in any way. If they are tightened, then one's mind becomes tightened and one's body tightens all the more. It can be harmful for one's body, too, and it can hinder one from holding one's mind in meditative tranquillity. If one makes one's mind a little bit airy, then maybe that makes one shake and tremble. Therefore, it's important to be at ease and relaxed in one's body and four limbs.

No matter how one sits, it's very good if the spine is straight. In the text that he composed, entitled Pointing Out the Dharmakaya, the Ninth Gyalwa Karmapa, Wangchug Dorje, explained why this is so and tells us: 'If the body is straight, then the channels will be straight. If the channels are straight, the winds will be straight. If the winds are straight, then the mind will be straight. ' And so, if the body is crooked, then the channels won't be straight. Therefore it's important to keep the body straight so that the channels are straight. If the channels are straight, the winds will be straight. In that case, the winds will not go back and forth but go as they should in the body. When hearing about wind, one takes it to be the coarse breath. In this context, the subtle wind is the quality of motion and movements in one's body. Motion is the characteristic of wind. If there's a lot of wind moving in one's body and if it isn't moving well, then many thoughts will arise in one's mind. And if there are many thoughts in one's mind, it will harm or hinder the ability to rest one's mind in meditative tranquillity. So, for this reason, in order to develop meditative concentration, it's important to hold one's body straight by sitting straight.

Furthermore, the Ninth Gyalwa Karmapa offers general instructions for the mind during meditation. He tells us:

'Do not follow after the tracks of the past.

Do not send out a welcome to the future,

rather, rest in equipoise in the present moment. '

'Do not follow after the tracks of the past ' refers to the fact that all things change from moment to moment 'things change every instant. Things go from being in the next moment to being in the present, and in the next moment they belong to the past. So, things change every moment; they go by in a momentary fashion. When looking at external objects, it can be difficult to see that external things change so quickly and in every moment. But when looking at one's own mind, one can see that thoughts first arise and then they go into the past, i.e., in one moment thoughts are in the future, in the next moment they are in the present, and then they are in the past. When they have gone into the past, they have ended. So, whatever thought there is, when it's in the past, it has ceased. Whether it's a thought of one of the three afflictions of hatred, greed, or delusion, or whether it's a good thought of faith and devotion, when it goes into the past, it's gone. Likewise, thoughts of the future concern things that haven't happened yet, so they, too, can't be objects of observation. One can only look at present moments. But present moments are extremely short and belong to the past very fast. It's good if one can rest in the short time of a present moment, without being distracted and leaning away from meditative tranquillity by following after thoughts. If one can look at the present, without many thoughts happening, then it's enough. This is all one needs to do in meditation. These are the general points of the mind that are taught by the Ninth Gyalwa Karmapa in Pointing Out the Dharmakaya.

In these instructions, the Ninth Gyalwa Karmapa explained the specific points of meditation practice and first said to use an external object of form for meditation. He offered advice on using the external objects of sight, sound, smell, taste, or touch as the bases for meditation. Then he taught tranquillity meditation without a support. Following, he presented instructions for practicing meditation by using the breath. I thought that it would be more beneficial to explain how to rest with the mind. If one understands how to rest with one's mind, how one's mind is, and what to use when meditating, then it would be very beneficial.

The Third Gyalwa Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, wrote a treatise, entitled Distinguishing Consciousness from Wisdom. In this treatise, he described the eight different collections of consciousnesses that we have. Which consciousness does one use when meditating? It would be beneficial for one's meditation to know which consciousness one uses when one meditates.

Of course, when one looks at the mind, it seems to be just a mind, but it can be divided into eight different types of consciousnesses. There is what we call 'the consciousnesses of the five gates, ' which are the five sensory consciousnesses that are gates to the world of perception. The way they work is that on the basis of the eye faculty there arises an eye consciousness that perceives an external object of visual form, and on the basis of the ear faculty, the ear consciousness arises and hears an external sound. Likewise, based upon the nose faculty, the nose consciousness arises and smells a scent. Also, the faculty of the tongue gives rise to the tongue consciousness that experiences a taste. Similarly, the body faculty gives rise to the body consciousness that experiences touch, which can be experienced as soft, rough, or anything like that. In this way, we have the five sensory consciousnesses.

Looking at the five sensory consciousnesses, it's interesting to ask whether they are conceptual or non-conceptual. Do they have thoughts or are they free of thoughts? The five sensory gates are called 'direct perceptions, ' i.e., they perceive an object directly. The eye consciousness directly sees a form, the ear consciousness directly hears a sound, the nose consciousness directly smells a scent, and so forth. But these consciousnesses don't think about what they perceive and don't discern, 'That's nice, ' or 'That's not nice, ' or 'This is good and that is bad. ' They are non-conceptual, i.e., by nature thought-free. They just experience, and that is how they are. They are naturally present and therefore we experience things through our five sensory consciousnesses. They can't and needn't be stopped; there's no reason to stop them. Their characteristic is to be naturally present and clear, i.e., the five sensory consciousnesses always perceive something and they are always clear. They are mind's characteristic 'thought-free, direct, and clear perception.

In contrast to the unstable five sensory consciousnesses, the next two consciousnesses are stable. Stable means that they are continuously present. The first is called 'the all-ground consciousness, ' alaya in Sanskrit. The alaya consciousness is like the source or place from which every appearance and experience arises and is just clear awareness. All the things one clearly sees and experiences arise from the alaya. Clear awareness is what is meant when talking about the all-ground consciousness.

The second consciousness is called 'the afflicted consciousness. ' It's also stable because it's always present. The afflicted consciousness is that aspect of mind that subtly clings to a self. It's not a coarse clinging to a self, rather, it's a subtle clinging to a self. Whether one actually thinks, 'Me, ' or 'Mine, ' or whether one is not thinking, 'Me, ' or 'Mine, ' in both cases there's a subtle clinging to a self that one may or may not be aware of. For example, if one is studying Buddhist philosophy and learns that there is no self, one develops certainty that there is no self. At that point one doesn't have the coarse thought, 'Me, ' but there's still a very subtle habitual or latent tendency to think, 'Me, ' which is due to the seventh afflicted consciousness. Later on, when a practitioner has developed deep knowing and attained higher levels of realization, clinging to a self is purified during tranquillity meditation. As a practitioner progresses, the afflicted consciousness is fully purified and not even present during post-meditation. But it's always present for ordinary individuals, who never stop having a coarse and subtle sense of a truly existing self.

The eighth consciousness, the all-ground consciousness, is mind's ever-present clear aspect. If one looks at one's mind's clear aspect, it can't be found or proven to exist anywhere. However, we don't recognize it as being empty of own existence. And so we see it as a self and think that things arise from what we mistakenly think is one's real self. This is due to the stable, all-ground consciousness that has the aspect of ignorance.

Which consciousness is used when engaging in tranquillity meditation? The sixth mental consciousness. A short summary: There are the five sense consciousnesses, sixth is the mental consciousness, seventh is the afflicted consciousness, and eighth is the all-ground consciousness. The sixth mental consciousness is said to be a conceptual consciousness, i.e., it's a consciousness that has a lot of different thoughts about what is perceived with the first five. It generates many negative thoughts, many neutral thoughts of indifference, and many virtuous thoughts, too. These various thoughts arise all the time and mix and combine thoughts that relate to the three times. There are thoughts about the future, about the past, and about the present. For instance, we think about what we saw with our eyes yesterday, we think about what we are going to see tomorrow, and we think about what we are seeing today. We mix all these thoughts into one with the sixth consciousness and see everything as being present. The sixth mental consciousness combines all three times and doesn't really distinguish between the past, present, and future.

Many different thoughts arise in the mental consciousness. In order to pacify thoughts in the sixth consciousness, one needs to let the mind rest peacefully within the expanse of the non-conceptual eighth consciousness. The eighth consciousness is like a big ocean, and the thoughts arising in the sixth consciousness are like waves. Sometimes thoughts are very powerful, like huge waves. These waves of thoughts cause one to accumulate karma, 'actions that bring results.' One gently lets one's powerful thoughts and conflicting emotions subside into the ocean that is one's eighth consciousness, rests at ease, and then thoughts are pacified. While easefully resting in the expanse of the all-ground consciousness, one has deep holding of tranquillity meditation.

As to deep holding of tranquillity meditation, many thoughts arise in one's mental consciousness. Sometimes they are pleasant thoughts and sometimes they are thoughts of displeasure or sadness. But, whatever sort of thoughts they are, one needs to take control and have mastery over them with mindfulness and awareness. If one manages, any thoughts will be pacified into the expanse of the all-ground consciousness. This means to say that the all-ground consciousness has the clear aspect. It has the clear aspect of knowing. It can know all sorts of things, and yet it doesn't give rise to coarse thoughts of pleasure, displeasure, or indifference. There's just the clear and knowing aspect. Occasionally thoughts arise in one's sixth consciousness. One needs to be able to settle these thoughts down. But one needs to have good mindfulness and awareness in order to do so.

When we talk about mindfulness and awareness, we are talking about two different mental factors that resemble thoughts or are a way of thinking. First there is mindfulness. Another translation for mindfulness is 'recalling,' i.e., remembering what one is doing. Mindfulness in this context is remembering, 'I don't want to lose myself to all my thoughts, ' or 'I don't want to have thoughts, ' or 'I want to be meditating now, ' or 'I'm meditating now. I shouldn't be moved by all these thoughts. ' If one has mindfulness, one recalls what one is doing and then awareness will naturally be present. Awareness means simply recognizing what is going on, i.e., knowing what one is doing. One knows that one is meditating and understands what is going on. Knowing what one is doing while doing it is being mindful. Then one will naturally develop awareness. But if one loses mindfulness, then awareness will automatically be lost. In that case, one won't know what one is doing and won't remember that one is meditating, rather, one will lose oneself to thoughts instead of letting them be. So, it's important to develop mindfulness and awareness. It's important to use mindfulness and awareness in order to be able to control one's sixth consciousness and in order to be able to develop deep concentrative meditation. So, having both mindfulness and awareness, a practitioner will be able to develop tranquillity meditation correctly.

Mindfulness and awareness are extremely important. The Son of the Victors, Shantideva (the 8th century Buddhist scholar and saint) spoke about them in The Bodhicharyavatara and taught:

'All of you who wish to control your mind, develop mindfulness and awareness, even if you have to risk your life. I join my hands in prayer that you develop mindfulness and awareness. '

So, if one wants to be able to control one's mind, to protect one's mind, Shantideva said that one needs to develop mindfulness and awareness. It's very important, which is why he stated that he joins the palms of his two hands at his heart in prayer and begs us to make sure that we rely upon them.

The great scholar and teacher Dakpo Tashi Namgyal (who lived from 1511-1587 C.E. and authored two classical Mahamudra texts, entitled Moonlight of Mahamudra and Clarifying the Natural State) spoke about mindfulness and awareness and taught that one should not be too tense about them, rather, one should let them be vast and expansive. One is tense and uptight when one thinks, 'Now I have to be mindful, ' or 'Now I shouldn't be thinking. I'm trying to meditate. ' Practicing like this will not be beneficial. One needs to be open and vast and not squeeze one's brain. All one needs to do is not forget, rest relaxed while alert, and not forget what one is doing. One shouldn't squeeze, push, or pull at one's practice and try to be tight about meditation, rather, one should have mindfulness that is open and vast. It will be very good if we have relaxed and expansive mindfulness.

If we practice tranquillity meditation in this way, we are very relaxed and rest like that. Here it is called 'tranquillity. ' A more literal translation is 'calm abiding,' which consists of two words, 'calm ' and 'abiding. ' The term 'calm ' means simply letting all thoughts be pacified; the term 'abiding ' refers to the stable aspect of resting. This is what we mean by the practice of tranquillity meditation. -- Thank you very much.

Dedication

Through this goodness, may omniscience be attained

and thereby may every enemy (mental defilement) be overcome.

May beings be liberated from the ocean of samsara

that is troubled by waves of birth, old age, sickness, and death.

By this virtue may I quickly attain the state of Guru Buddha, and then

lead every being without exception to that very state!

May precious and supreme Bodhicitta that has not been generated now be so,

and may precious Bodhicitta that has already been never decline, but continuously increase!

May the life of the Glorious Lamas remain steadfast and firm.

May peace and happiness fully arise for beings as limitless in number as space is vast in its extent.

Having accumulated merit and purified negativities, may I and all living beings without exception

swiftly establish the levels and grounds of Buddhahood.

'this world

bristles with thorns

yet there are lotuses '

-- Kobayashi Issa

All photos were taken and graciously offered by Lena Fong. Thank you, Lena, for everything! -- The teachings were presented at Vajra Vidya Thrangu House, Oxford, in 2006; translated by David Karma Choephel, transcribed and edited slightly by Gaby Hollmann, who is solely responsible for any mistakes. Copyright. Munich and San Francisco, April 2010.