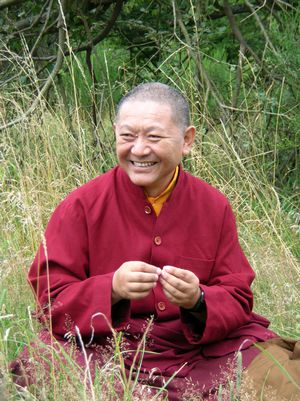

Venerable Ringu Tulku Rinpoche

Buddhism & Ecology

Presented on March 12, 2009 in the Freiherr von Stein-Saal of the Bezirksregierung Münster.

Hosted by the Advisory Council for Foreigners of the city of Münster,

in collaboration with the Sozialpädagogisches Bildungswerk & Karma Sherab Ling.

As you probably know, the main philosophy of Buddhism is the understanding of interdependence, what we call "dependent arising." This means that there is always dependence among everything. Nothing exists and nothing stands on its own without the effect of others, i.e., everything is dependent upon everything else.

In Buddhist terminology, we speak about the content and the container. Living beings and people living on earth are referred to as "the content," and the earth and all its elements are referred to as "the container." The contents cannot exist in the absence of the container. Life on earth and the survival of living beings, especially of humans, very much depend upon the wholesomeness of the world and the health of the environment. The health of the world and the essence of the earth are very important for every one. Therefore people have the responsibility of keeping the environment in which they live in a good condition and of caring for it in a proper way.

We know that human beings have slightly different attitudes toward the earth, elements, and nature and in recent years many people think that they have more and more rights to conquer, exploit, squeeze, and take everything out of the earth. They think that the more they take, the more they can exploit it for short-term benefits and that they can conquer the elements. From the vantage point of interdependence, it becomes very difficult, though. If one keeps taking, one has picked the fruits, but if one doesn't give back what one took or if one doesn't nurture nature, at a certain stage it loses its potential to give us what we need. Who suffers then?

There have always been efforts, especially in the Buddhist world, to try to respect the truth of interdependence. In Tibet - I'm sure elsewhere, too - we used to have protective reserves in every monastery, like forest reserves, that shielded the nearby and distant forests, the water, and the animals. It was forbidden to hunt and fish within that specific area. Land was also regarded as sacred, in the sense that if one overly exploited it, then its capacity and ability to sustain us will deteriorate. I found out something very interesting. Many Chinese companies have been digging for mines in the mountains of Tibet. What they do is cut the mountains into pieces and slice off huge slopes with explosive dynamite. The local Tibetans say that their yaks' production of milk has diminished about 30-40% after this started happening and therefore they protest. I heard that the people of one small community said at a meeting that they would not allow this to happen and are willing to die for the cause; they have been involved in many battles and many people have been imprisoned by the Chinese as a result. Sometimes I feel that many of the protests that took place in Tibet recently are not only political but have a lot to do with protesting against the destruction of the environment.

Question: /Inaudible./

Ringu Tulku: I don't think that I have to speak about the dangers of global warning and all these things. I think you know about this better than I do. But I recently heard from scientists that it is becoming a very critical situation and that if the people in the world do not take very strong and decisive steps to stop this crisis very soon, then the consequences of global warming will become irreversible. The signs of ecological devastation and global warming are quite evident in many places, especially in the Himalaya Mountains. The great glaciers are melting at a rapid speed and the high mountain peaks that were covered with snow all year are now almost bare and black. This is affecting the water. I was told that the ice on the mountains of Tibet is just as old as Tibet and that's why it is called Böd-po, signifying ´the region of the grand mountains.' The ice is dangerously receding, which is mostly caused by the actions of human beings.

From the Buddhist point of view, it's not irreversible because everything can be changed - for better or for worse. Some people even believe that reciting prayers can change things. I don't believe that things change by just praying. There is a Japanese scientist, Dr. Masaru Emoto, who makes photographs of ice crystals. I think many of you may have read his books and have seen his photos. I met him in Barcelona and he showed how he made the photographs. He took water from different sources, put it on a plate with many tubes and 50 small holes, and placed the plate in a strong refrigerator so that the samples freeze. He then took photos with a strong camera. He found out that anybody can influence water and that if it is taken from a pure area, countryside, or is holy water, then the crystals become diamonds. If the water comes from big cities or polluted areas, then the crystals are really fragmented and strange, like angry crystals. He tried to prove that if people say prayers to water that comes from cities and not pure areas, then the water changes. Not only that, but if one writes down positive words, like "love" or "gratitude," and places the paper on a bottle of water, then it changes the water. But if one writes down negative words, like "anger" or "hatred," and places the paper on a bottle of water, then it changes the water, too. What he is saying is that water can be affected by prayers, by a positive attitude, by positive words. If that is the case, he argues, then those factors affect living beings, because their body mostly consists of water, something like 80%. He said that the earth consists of the same percentage of water. He proposes transforming the earth by distributing bottles of healed water to all schools in the world and in every language. When I heard him, I thought to myself that he must have lost his confidence in atoms. But, that is one way of seeing.

I think prayer is a very strong factor, because it is a heart-felt wish and invokes blessings. If one's mind has positive energy, whatever one calls it, then it must have an effect. Especially, when one recites prayers from one's heart, then one is making a strong aspiration, a strong wish, and that starts the process of doing something and one's actions. But, from a Buddhist perspective, just praying and wishing don't go that far, because everything depends upon causes and effects that always are associated with actions.

Buddhists speak about karma, ´the law of cause and effect,' very much. Karma isn't about waiting for results of actions carried out a long time ago to occur and isn't about hoping that some outer being will make things go well. Karma is the Sanskrit term that means ´action.' This means to say that if one does something, it will have an effect and if one doesn't do something, nothing will happen. If one does something positive, then a positive result will come and if one does something negative, a negative result will come. If one sows a seed that brings forth a plant with sweet fruits, then sweet fruits will grow and if one sows a seed that brings forth a plant with bitter fruits, then bitter fruits will grow. From the Buddhist point of view, it's very important that everyone together starts trying to become aware of causes and effects and starts to take necessary actions. If one doesn't do that, then nothing will happen.

You know, human beings can learn if they want to. India, for example, is quite dirty. People throw their garbage on the ground and leave the shells of the peanuts they eat lying around in the train compartments. I thought that was how it should be. My western friends who visited me picked up things that I threw down and put it in their pockets. I thought this was going too far. When I came to the West, I saw that everything is so clean and I understood why, because everyone puts their rubbish in their pocket and empties it in the next dustbin. So many things are destroyed in Indian trains, so signs are posted, saying: "This is your property. You must take care." There is the story that there was a mirror in the bathroom of a train compartment that someone took home. He put up a sign in its place, stating: "I've taken my share." Having a mentality like that and taking what one thinks is one's share cause the problem. Therefore, the most important thing is to be able to see not just what one wants and not just what is momentarily profitable for oneself, but to see what is good for all people and for the future of one's children. That's how one should see things and act. When one's attitude has changed, then everything changes. But it means being aware, which isn't something a government is in charge of. Each and every person has to have the right way of seeing and a certain kind of clear understanding of the meaning of relationships and their effects.

People often comment, "Oh yes. So many airplanes and cars are causing pollution. Lots of people travel by airplane. They fly to Asia, sometimes to meet Tibetan or Buddhist teachers." People even tell me, "Maybe you should tell them to stop doing that." I don't think it's practical to stop travelling by plane. If I didn't travel by airplane, it would take me three years to come here from India - if I ever arrived. That isn't a practical solution and isn't really necessary. It's not a matter of going backward, but of going forward. Since man invented the technology to make airplanes and cars, maybe he can discover a technology to make them much more efficient in the usage of gas and fuel and to be less polluting. Gadgets and technologies are improving all the time. In the same way, when one sees the problems, it's possible to solve them by improving the situation. I don't think that technology is the problem all the time, rather the way one uses it. I think much has to do with one's attitude.

In a conversation with Josef, he told me that a research had been carried out recently and it was found that the Bhutanese are one of the happiest people. Actually, the King of Bhutan wrote a book and made a proposal three years ago. He wrote that all nations are always thinking about gross national production and that is their focus of attention. He asked, "Is that our only vision?" He argued that Bhutan also wants better gross national production because they want a better life and happiness for all people. He wrote, "The reason we want economic development is so that people become wealthier and happier." He continued that it is a wrong way of analysing how happy the people of a country, nation, and the world are by just measuring their production. He proposed that countries should not only look after their gross national production, but they should also look after national happiness.

There have been international conferences on gross national happiness. The first conference of this kind was held in Bhutan, the second in Canada, and the third last year in Thailand. I happened to be at that conference. It was very interesting, because it's a slightly different way of looking at things. The main issue is looking at what one really wants. Just more money, just more cars, or more happiness and more well-being for everyone? It's not always a matter of high living standards for people to be happier, but that they also have an easier life.

Since 1990, I've been visiting Ireland every year. In 1990, Ireland was economically one of the poorest countries on earth. People had very small cars, the roads were small, and there was much unemployment, but everybody had their little flat, their little house. One could buy a house in Dublin for about 20,000 Pounds. I should have bought one then, but of course I didn't have the money. One could buy a lunch consisting of a little soup for 1 ½ Pounds. But everybody went to a pub at 6:30 or 7:00 and came out singing at 11:00 every night. People were kind of happy and everyone went to church. The churches were completely full on Sundays, not only the inside, but also the courtyard outside. The country became better and better every year and slowly the economy boomed. Ireland was something like the tiger of Europe. There was more and more money and everything became more and more expensive. When I was there last year, I saw that the situation had changed. Everybody has a job and everybody has lots of money, but life is so difficult. Even if one has a very good job, one cannot find a flat in Dublin that one can afford. One has to live far outside the city and has to travel a long distance to and from work. Although one has lots of money, I don't think life is easier, rather it's more difficult, not necessarily from the psychological side, but from the practical side. Therefore, I think it's important to look at things in a deeper way.

We human beings are supposed to be very advanced and we think that we are the most evolved, more so than other species on earth. But we still have all animal instincts. We attack each other, we are competitive, aggressive, greedy. I don't know how much better we act than people and animals living in the jungles.

From the Buddhist point of view, it is said that every living being has Buddha nature. This doesn't mean to say that one is automatically kind and good when one is born. It's just saying that one has the potential and there is the possibility to be compassionate and wise. Yet, one has the instinct and habitual tendency of being aggressive; it's almost biological. But one has the possibility to evolve out of that, the possibility of being altruistic, and of developing to be better than one is. Because everyone has the potential to become compassionate, to have love, and the clarity of mind to reason and to see clearly, it is possible to evolve from the habitual tendencies of being aggressive, greedy, and ignorant. One can become enlightened. One can bring out that nature of loving kindness, compassion, and wisdom. One has the possibility, and that is the way to progress, as human beings to progress further. This doesn't mean getting things, being aggressive, and acting like animals in the jungle, but having a wider view of what one is doing and a wider vision of what one really wants. It's not a matter of just wanting things, but of wanting what is good for oneself and for everybody else's future, too.

If one learns to think this way, like putting one's rubbish in one's own pocket, then I think one is creating a golden age. This is the understanding of all world religions when they talk about heaven, higher possibilities, and a better world where there is compassion, wisdom, love and compassion for others. So, if one wants to change the world into a better place, one has to change oneself. If one can start doing that, then I think it will affect everything around.

Sometimes people think that it's impossible to change things and argue that the world has been the way it is for a very long time. In a way, it is like that. In a deeper sense, it is difficult because one doesn't want to change. If one really wants to, I don't think it's that difficult, because one can decide for oneself:

"From today on, I'm not going to harm anybody.

I'm going to treat everybody equally."

If everybody started being like this, that's how simple it would be to create heaven on earth. Therefore, one's prayers and one's motivation should be for that. In Buddhism, we have the concept of a Bodhisattva, who is someone who never hesitates to do what he can so that others are free of suffering and experience happiness. One should strive to be like that.

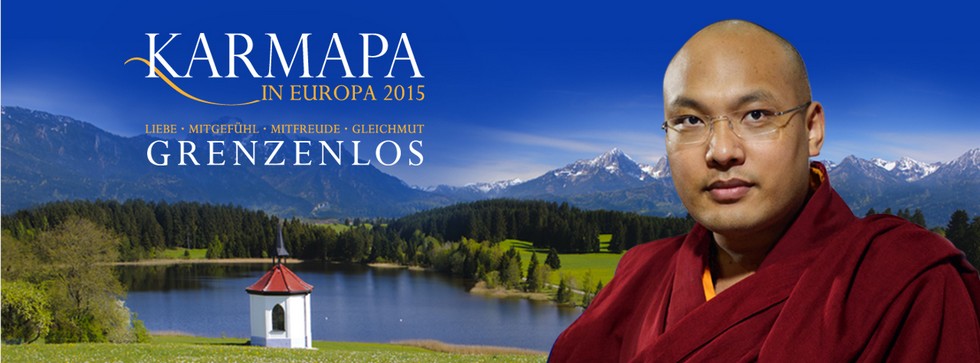

I will stop here, but if you want to know more about the way leading scholars from all schools of Buddhism - Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana - look at ecology, there's a website in the English language that you can visit; it is ecobuddhism.org. The book will appear under the guidance of His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama and His Holiness the XVIIth Gyalwa Karmapa this May. If you have any questions now, please ask.

Question: /Inaudible, therefore transcribed in reliance on the translation:/ "Buddhists speak about creation from the viewpoint of causality, but sometimes it is said that animals have more compassion than humans. Would you please say something about this?"

Ringu Tulku: From the Buddhist point of view, all sentient beings - ´sentient beings' referring to all living beings who have a consciousness - have the capacity to develop wisdom, compassion, and all their positive sides. It isn't really necessary for all human beings to be equally good and equally bad and for all animals to be equally good and equally bad. There can be very great Bodhisattvas among the animal world. The Jataka Stories recount many former lives of the Buddha as an animal, as a bird, as a deer, as a rabbit, all having had great compassion and wisdom. It shouldn't be generalized, though. That's the understanding.

Next question:"There are different views about inanimate matter, like stones. I saw a movie that showed that people believe that stones have consciousness. Does a stone and inanimate matter have consciousness?"

Ringu Tulku: I think this has a lot to do with the modern way of being respectful toward nature. Making everything - water, rivers, lakes, springs, trees, mountains, and things like that - sacred is one way of protecting nature. Thinking that something bad will happen if one disturbs nature is a general way. Sometimes people think that spirits live in rocks, in trees, and in things like that. From the Buddhist point of view, it's not a matter of thinking that everything has a mind or consciousness, yet it's not impossible. It's a matter of identifying that. By strongly identifying with a rock, or a door, or a window, or a pillar, one kind of becomes one with that object. There's a story of somebody who identified with a door and he felt very bad whenever it was banged. It has more to do with mind's creativity, of being able to identify with almost anything.

Next question:"Should one be a vegetarian according to Buddhism? Does one have bad karma by eating meat?"

Ringu Tulku: Yeah. It's like this, from the Buddhist point of view, eating meat is very bad; eating vegetables is much better. It's not the case that one cannot become a Buddhist if one doesn't become a vegetarian. The practice of Buddhism is not limited to anything. One doesn't have to be a monk or nun, one doesn't have to be a vegetarian, one doesn't have to be this or that or anything. Buddhism makes no restrictions on anyone. It's important to know that one's eating habits, one's clothing habits, and any other habits one has are not barriers. Being a Buddhist doesn't mean one is supposed to be vegetarian. There are lots of Buddhists and non-Buddhists who are vegetarians. During the Buddha's life, he gave many teachings on how good it is to be vegetarian, but he didn't set down rules that his monks must be vegetarian. He told them: "You should eat whatever you are offered. You cannot say, ´I will eat this and won't eat that.'" At that time in Indian society, the high-caste Brahmins were vegetarians and the low-caste Shudras were non-vegetarians. The Buddha did not want his followers only to have the same habits as the higher caste. So, that's the way.

Nowadays, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who comes from Kham in East Tibet, and His Holiness the Gyalwa Karmapa were strong meat-eaters. But they became vegetarian and strongly promote vegetarianism. There is a Tibetan youth group in India that promotes vegetarianism. They made a shocking video on how animals are killed and gave it to all Tibetans. Whoever saw that video became vegetarian, at least for a short time. I have resisted looking at that video so far.

Next question:"Can you give us a practical instruction on how to become aware of ecological dependent arising. I understand the theory but have trouble becoming aware of it in daily life. What should I focus my attention on and how can I notice?"

Ringu Tulku: Give an example.

Same student:"When it is said that everything is dependent upon other things, I want more insight and want to get a taste of interdependence."

Ringu Tulku: Having a nice garden depends on how well the garden is tended and cared for; it depends on how much you work on it. That is interdependence. If I see that you have a very nice garden, that all plants and flowers are growing and the lawn is mowed, then I can see and then say to myself, "Yes, he has really been working on his garden." If not, I know that you haven't worked on it. A nice fruit tree will not grow by just sitting there and wishing that a nice fruit tree will grow in one's garden. If one wants a nice fruit tree in one's garden, one has to go out and find a good sprout, plant it, and do what has to be done so that it grows. That is one's relationship and interdependence with one's garden. Of course, one has to see the connection between one's actions and their results. I think that's the main thing. The world is like our home. One's relationship to one's home has to do with how one treats one's room, or flat, or garden.

I think we will stop here. Thank you very, very much, especially very many thanks to the organizers.

Dedication

Through this goodness may omniscience be attained

and thereby may every enemy (mental defilement) be overcome.

May beings be liberated from the ocean of samsara

that is troubled by waves of birth, old age, sickness, and death.

By this virtue may I quickly attain the state of Guru Buddha and then

lead every being without exception to that very state!

May precious and supreme bodhicitta that has not been generated now be so,

and may precious bodhicitta that has already been never decline, but continuously increase!

Long Life Prayer for Ringu Tulku,

composed by H.H. the XVIIth Gyalwa Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje

The most peaceful essence of clear light, arisen as the changeless form of illusion,

free from any sign of age and decay, may he live forever as the Buddha of long life.

"As the bee collects nectar and flies away without damaging the flower,

or its colour, or its scent, so also, let the monk dwell and act in the village

(without affecting the faith, and generosity, or the wealth of the villagers)."

-- The Buddha, Verse 49 from the Tipitaka

Sincere gratitude to Mr. Spyros Marinos, Chairman of the Advisory Council for Foreigners, for having hosted & sponsored this event so very generously. A very special "thank you" to Mara Stockmann, Director of the Sozialpädagogisches Bildungswerk in Münster, for her very cordial support. Special thanks to Wolfgang Werminghausen for having made the recording available to us. A very special "thank you" to Annette Bungers for her exceptionally good simultaneous translation of English into German. A heart-felt "thank you" to Josef Kerklau for having organized this event, for the photo of Ringu Tulku that he took while on a walk in the countryside near Kamalashila Institute in 2005 & for having proofread this transcript carefully. Transcribed & arranged by Gaby Hollmann, solely responsible for all mistakes. Copyright Ven. Ringu Tulku & the mentioned beneficiaries in Münster, 2009. All rights reserved.

Give the wisdom of loving kindness and compassion to the world!